About

the research

Bateson's Cosmos

Here you can explore the outcomes of Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec iaculis nisi in gravida tristique. Nulla lacinia diam vitae odio tincidunt, eu semper nisi fermentum.

Steps Around a Theory of Action: Notes on Seven Bateson Conferences

On the making of “Steps”

Dulmini Perera

What?

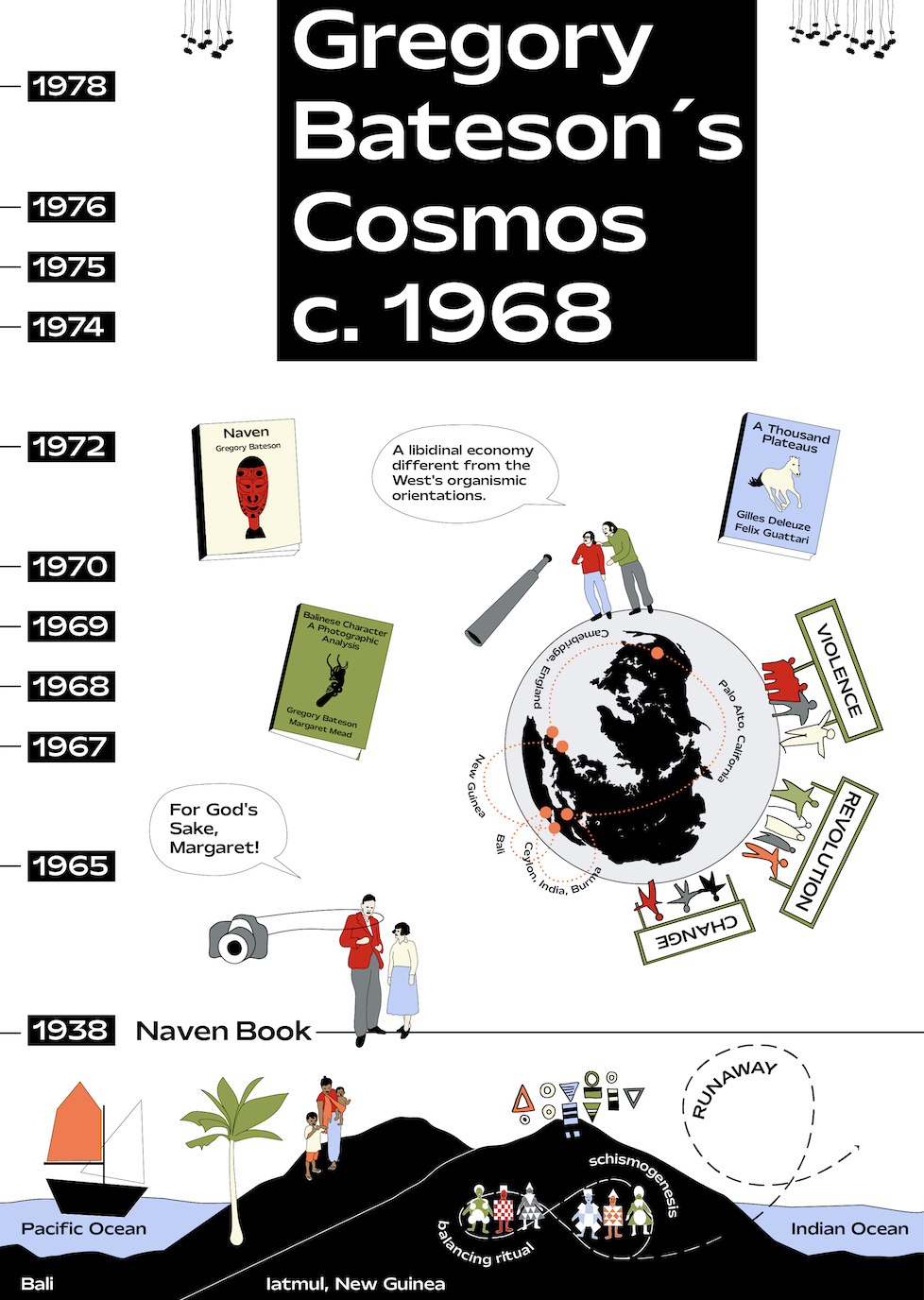

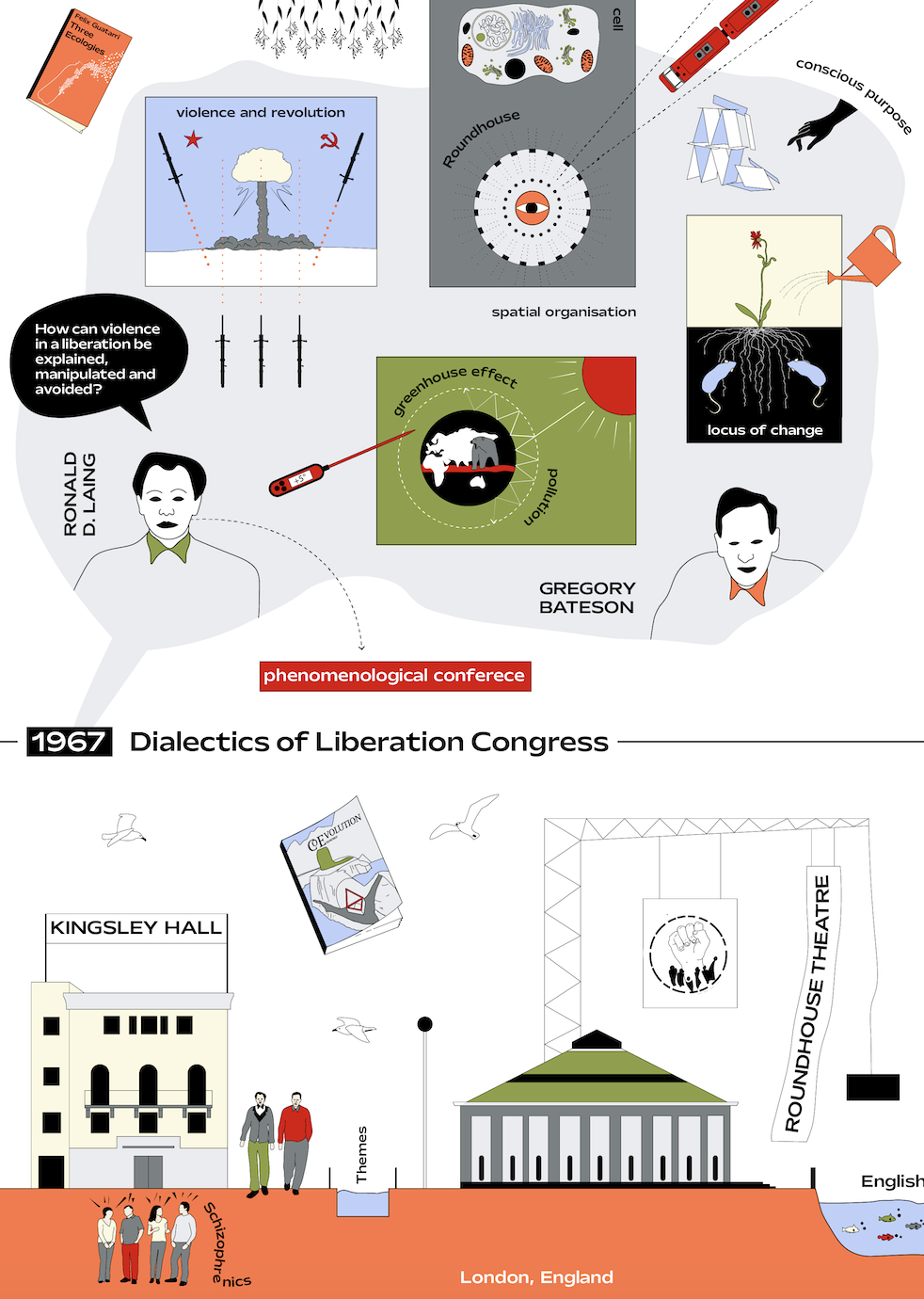

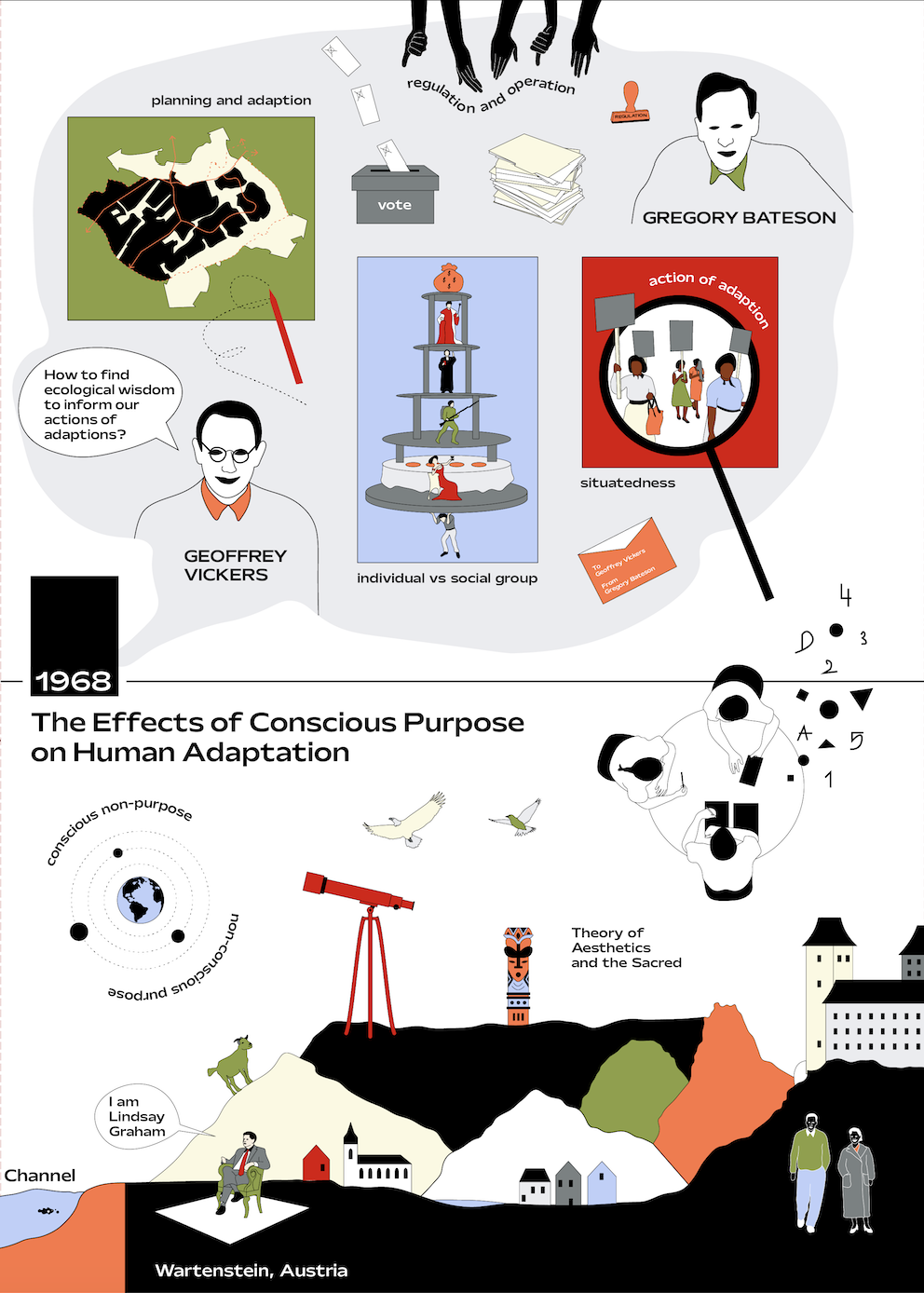

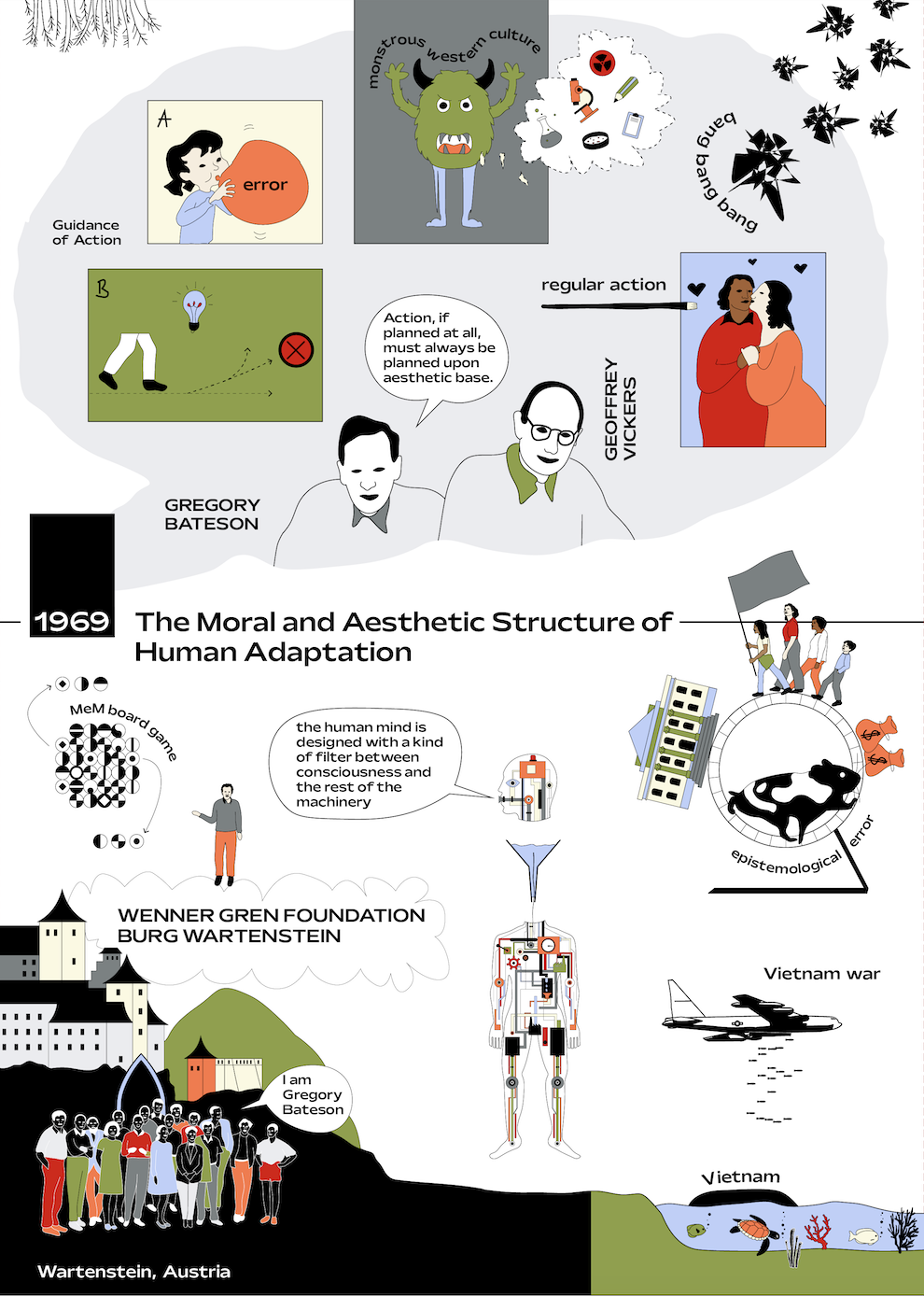

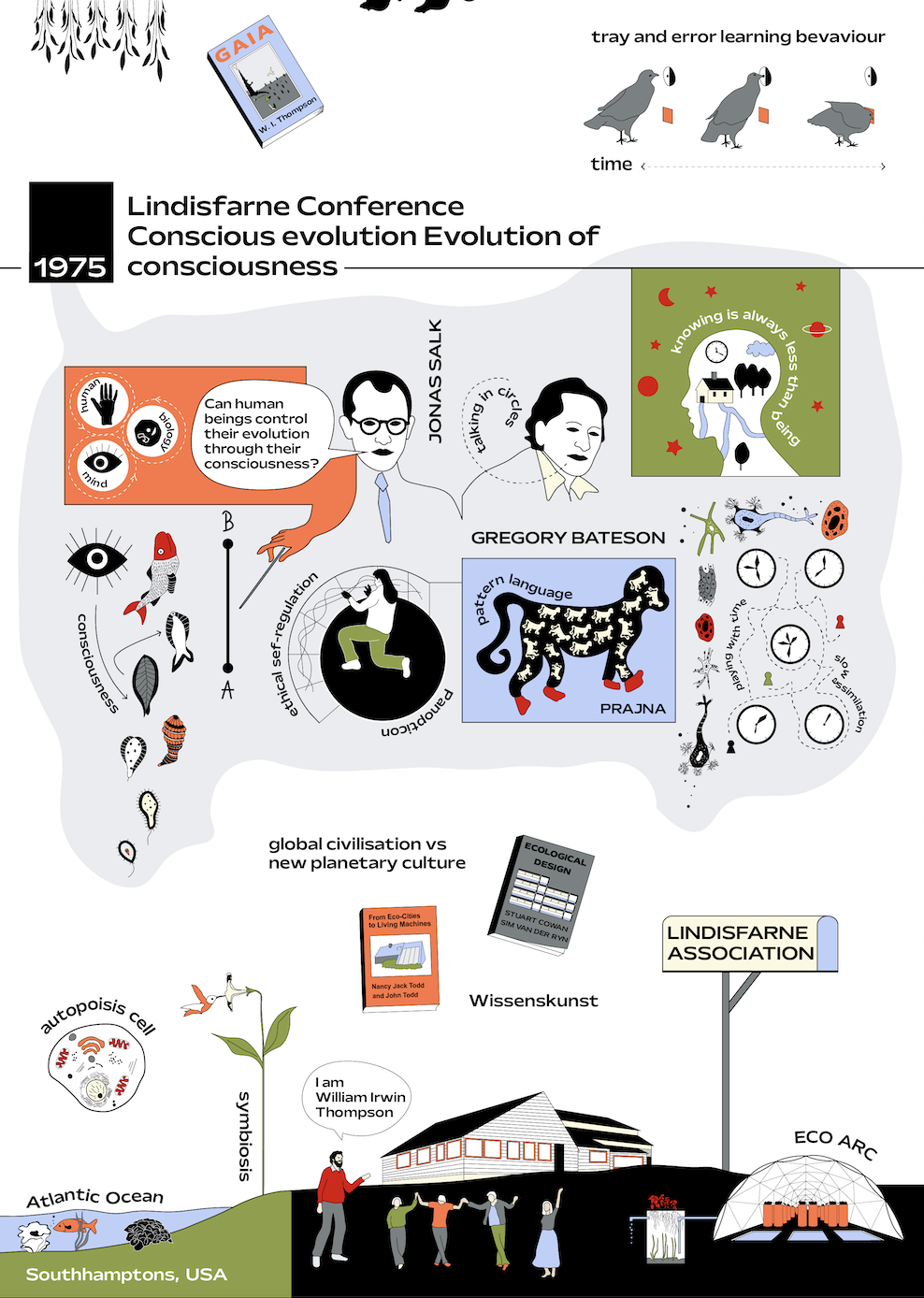

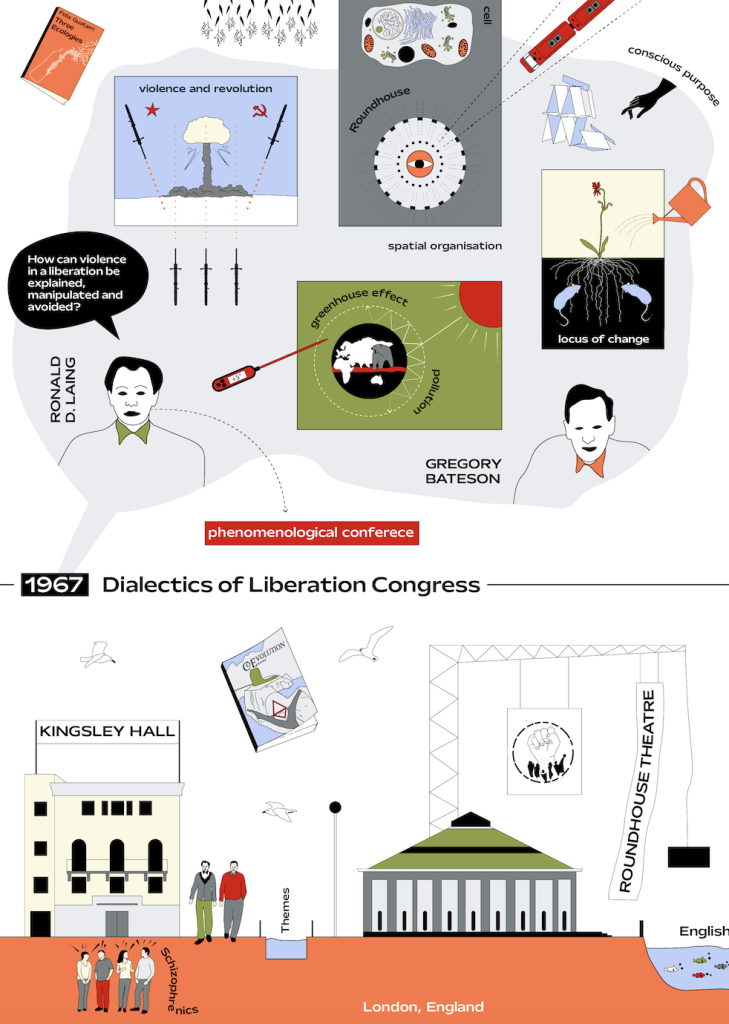

Steps Around a Theory of Action is a collection of short introductions to a series of hitherto unexplored conferences where Gregory Bateson explores questions about acting within the ecological crisis. The graphic titled Bateson’s Cosmos c.1968 and the series of short texts on the conferences draw significantly from many primary sources, including transcripts, letters, reports, and audio and video recordings in multiple archives.

Several things prompted my interest in developing this output. The first was a comment from a reviewer of the project proposal who mentioned that the project contained a promise to open Bateson’s archive in ways that can help move beyond the contemporary crisis of imagination affecting practices and practitioners acting within the ecological crisis. The second was the experience I have previously had in trying to teach Bateson’s ideas to students mainly from various design disciplines who found it difficult to understand the richness of Bateson’s somewhat transdisciplinary and abstract writings partly due to their inability to visualize or better understand the specific historical, geographical, intellectual contexts through which they emerged. The third was a short exercise at the Santa Cruz Diner conducted by Jon Goodbun during the archival visit, where he had prompted the rest of the archive team members to think of the specific relationships between landscapes and thoughtscapes or how Bateson’s movement across contexts influenced his thinking and how one could think of Bateson’s movement and his intellectual project in relationship to one’s movement and concerns. At this workshop, I produced a diner sketch containing the outlines of the drawing that the reader will encounter here today.

During my brief time at the archive, I saw how, as a series of events, the conferences opened up different ways to access Bateson’s „ideas“ through networks consisting of sites (environmental, institutional, etc.), people, objects that in some ways inspired Bateson’s ideas and vice versa became contexts where some of the ideas found embodiments as well as critique. Moreover, the records of these events are lively, conversational, and playful, which are aspects of Bateson’s work that are often less visible in his published monographs. Steps Around a Theory of Action is an invitation, a starting point for architects, designers or any curious reader to access a part of Bateson’s cosmos of ideas in the post-1967 period while keeping an eye on lively contexts of their production.

How?

As we started to work with the material, the four members of the archive group, Jon Goodbun, Simon Sadler, Ben Sweeting and myself, had various levels of previous experience with Bateson’s work, different research interests as well as research questions, all of which have influenced the different ways of narrating the events. These specificities are mirrored in the voice and style of the short texts, which I have explicitly preserved as a way of maintaining the “multiple descriptions” valuable to an ecological understanding, as Bateson reminds us. In addition, it was apparent that the stories we wanted to tell, particularly the relationships that form those stories, could not be conveyed in mere words. Nor was it about merely telling the story but rather about making it available so the readers can find their way in, interact with it and develop their trajectories of interest. As such, based on the textual summaries provided by the rest of the group members and with further consultations with the archives, i have worked on developing the drawing titled Bateson’s cosmos, which was hand sketched by me, redrawn and reframed in a digital reproducible form by Leonie Link, Florian Tudzierez and made into an interactive source with the help of Paola Ferrari and Stefanie Huthoefer. I am particularly grateful to the Weimar team for their contributions and for the feedback related to the difficulties in understanding the drawing that paved the way towards developing iterations.

Why?

The engagement with the archive, both as a group and individually, made it apparent that an engagement with Bateson’s post-67 work was significant to questions related to (design) action that prefigures our research project. It should be noted that Bateson had already talked about action and applied knowledge in different ways through different moments in his work. It would be erroneous to bind the breath of his ideas around action to this period. However, there are conditions specific to this conjuncture that influenced the nature of Bateson’s exploration, such as the surging interest in both the ecological crisis and cybernetics, as some of us have argued in work that predates this project. For example during this period Bateson became explicitly involved in questions of environmental and ecology due to his work at the University of Hawaii(1965-1972), particularly as a member of the Ecology and Man Committee. He also attempted to address the question of action in a more systematic way as evinced in his interest in developing “a theory of action” or the search for an “applied epistemology” that is ecological.

Through our work, we have shown how Bateson’s presentation and responses at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress(1967) are particularly telling of Bateson’s concerns against particular kinds of action and how the conferences that follow show glimpses of Bateson’s efforts of trying to work with various practitioners and practice contexts (including architecture and design) who were trying to develop alternatives.While each of the archive team members read the 67 moment and what follows in Bateson’s praxis in different ways, as “a turn towards wise-action” (Goodbun), “a particular kind of an organic intellectual praxis better suited to think through the violence generate by techno-environmental practices (Perera), as an “ecological politics”(Sadler), “as a move away from systems approaches driven by conscious purpose”(Sweeting), collectively we make a case as to why this moment is worthy of paying attention to, by anyone interested in understanding how Bateson’s work contributes to thinking about questions concerning design action.

Moreover, the contexts of the conference events and related networks mapped closely become ways of rendering visible the philosophical materialism that is part of Bateson’s „ecology of mind“ (a concept that is sometimes read-only as a form of ‚idealist‘ oeuvre around „pattern“). Put differently, this diagram and narratives foreground what Bateson identified in the 1969 Princeton conference as the „territories of minds“, which encompass objects as well as thoughts, bodies as well as ideas. To suggest that there are territories of minds would suggest how the broader insanity and crisis of ideas/imagination were enfolded into the extended motor apparatus that generates ‘ideas’ spread across biological, neurological, technical, evolutionary space and time. Architecture and design and its related practices, objects, and practitioners all form a significant part of these territories, as the image of Bateson’s cosmos goes on to demonstrate.

The networks of sites, objects, and people that become part of Batesons’s Cosmos also suggest an alternative history of post-WWII cybernetic explorations, one radically different from those better-known histories related to military-industrial logics, global techno-environmental managerialism and the countercultural beginnings of Silicon Valley liberalism. Interested readers may find here a history of ecological cybernetics that contains unfinished prototypes, less defined ideas about what technology, information and design should be, as well as open-ended conversations on ecology, action, and open systems that, in many ways, prefigures some of the contemporary concerns and discussions around technology, coloniality, violence and action.

I sincerely hope you find this resource helpful for your own concerns, questions and struggles related to acting within the present ecological crisis!

Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research

Symposium on Reconstructing the Ecology of a Great City, October, 1970

Simon Sadler

Seeking “useful insights” from ecologists at a moment when ecological and environmental discourse was cresting (notably in that year’s first Earth Day), Gregory Bateson was invited by Jaquelin Robertson, Director of the Office of Midtown Planning and Development, on behalf of the New York City Mayor John Lindsay, to organise a symposium hosted in 1970 by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research.

Among the participants, Mary Catherine Bateson, focused at the time on inter-generational linguistics and communications, compared the event with the Wenner-Gren symposium ‘Consciousness and Human Adaptation’ held two years before—“the first time I ran into some of these ideas”. She was one of the most energetic contributors to the symposium, as was Warren Brodey, a psychiatrist and avant-garde cyberneticist then leading his experimental Ecology Tool and Toy corporation. Fred Kent, a former student of Margaret Mead and William H. Whyte, had organized the first Earth Day in New York City in collaboration with the Office of the Mayor, closing Fifth Avenue to automobiles and seeing over 100,000 people attend an ecology fair in Central Park; in 1968, he founded a New York City street academy for high school dropouts supported by Citibank. Greatly influenced by the thought of Gregory Bateson, Frank Gillette was a founder director of the 1969 Raindance video collective and, in 1971, of the countercultural media magazine Radical Software (‘radical software’ was Bateson’s term for reformulating our understanding systems behavior through the indeterminism of cybernetics).1 American marine mammal biologist Kenneth Norris was famous for confirming that dolphins use sound transmission to see, and for co-founding SeaWorld. Roy Rappaport was an ecological anthropologist who coined the distinction between a people’s cognized environment and their operational environment, that is, between how people understand their environment and how an anthropologist interprets the environment through measurement and observation. Albert Scheflen, a professor of psychiatry based at the Bronx State Hospital, studied human communication and behavior patterns across different ethnic backgrounds. Hsi Fong Waung, a post-doctoral physicist studying ecology, and Lawrence Slobodkin, a pioneer of modern ecology, were based at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. Bateson considered inviting Christopher Alexander, whose 1964 Notes on the Synthesis of Form he was just reading and, at Mary Catherine Bateson’s suggestion, urban sociologist Richard Sennett. Pushed for space at the event, Bateson instead patched his readings of Alexander and Sennett into the version of his position paper for the symposium published in Radical Software as ‘Flexibility and Ecological Planning’.

What we might imagine as being the most urgent environmental tasks of c. 1970—waste, pollution, and transit, the topics of extensive EPA presentations at the meeting—were pretty much subsumed during the course of discussion by the challenges of social ecology, bottom-up expertise and agency, and heterarchic governance. Bateson understood the built environment as a conduit relaying information from which we “pickle” ideas (Bateson’s term)—some ideas ecologically valuable, and some fallacious, like the possibility of linear, Cartesian organisation. Countering any excessive pickling and centralising potential of cities, the discussants sought the city’s capacity for ‘high variety’, its “systemic room-for-manoeuvre” (to borrow Jon Goodbun’s summary of Bateson’s position paper). Mary Catherine Bateson, for instance, advocated for parks, schools and day care centers as sites of inter-generational planning founded on a shared delight in children. Warren Brodey and Frank Gillette advocated for the deployment of new locally-networked communications technologies like cable television and computing. Not much was said about the usual aesthetics of urban design—style, massing, and so on—but the group reached a more abstract aesthetic epiphany about how, through the patterning and perception of the city’s circuits, its citizenry can realize the potential of social ecology, urban politics and environmental design to become “unstuck”, as Bateson put it, or an “ecological toy”, to use Brodey’s concept.

In its final couple of days, the symposium felt it was pinpointing the qualities of this new “ecospace”. Conventionally, organisms—here, city dwellers—map their territory through ‘intensive’ (inward-looking) and ‘planar’ geometry, giving them a limited view of the world. But the city planner must command an ‘extensive’ (outward-looking) and ‘spherical’ geometry, which unfortunately does not always intersect with the worldview of other citizens. Urban ecospace would be an empathetically political space, “spaces which have a capacity for playfulness” as Brodey put it, an epistemological bridge between intensive and extensive worldviews, allowing the city to be experienced by citizens as more than just “a hassle”. “This is what opening Fifth Avenue for pedestrians is”, Mary Catherine Bateson recalled of Fred Kent’s Earth Day experiment. The symposium concluded in de facto agreement with the premise Bateson attempted to outline at the outset—urban form must be that circuit structure, like a wave in nature, relaying to its inhabitants the potential for interaction, bringing us together as though in the “one interacted union” of the “Dance of Shiva”. Albert Scheflen added that this new ecological thinking works downwards, from the higher level of the urban ecosystem, whereas old ecological thinking worked from the bottom up. When restructuring the ecology of a great city, we might then deduce, we can better work from the whole to the part than from the part to the whole.

Gregory Bateson describes multipurpose use—in nature, and now in cities—as “the biological tendency”, and it seems that the 1970 Wenner-Gren symposium gave Robertson an eco-theoretical framework for the mixed-use principles that became a hallmark of postmodern urbanism (after, say, a park-is-a-park, a highway-is-a-highway functional and social separations dogmatically imposed on New York by the modern planning of Robertson’s predecessor Robert Moses). Robertson’s Office of Midtown Planning and Development devised zoning provisions that allowed new skyscrapers to house a mix of offices, apartments, and retail stores, encouraging developers to provide ground-floor amenities in exchange for the right to build additional square footage. As a result of this work, in the opinion of the leading postmodern architect Robert A.M. Stern, it became “impossible to build a significant building in New York without serious consideration of its contributions to the city’s

urbanism”, concluding “Jaque prevented New York from destroying itself”, it was through a vision and a policy of the urban as something “sacred” (as Gregory Bateson alluded at the symposium), bigger than individual and commercial self-interest.

It’s curious that there was seemingly not a single mention at the symposium of Jane Jacobs and The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), especially given her interest in biological systems thinking and self-organization. Then again, if Jacobs saw in Robert Moses the supreme bogey of the greatest American city, Robertson and the Wenner-Gren group were impressed, if critically, by Moses’ work. Robertson—from an aristocratic family, and enroute to a distinguished career in practice and education—belonged to a cadre of architects around Mayor Lindsay who believed that design was a high public calling. The megalomaniac example of Moses had to be reinvented through greater efforts at coordination between agencies, Robertson believed, and by efforts to devolve political power to communities. This was to be the subject of a conference convened by Gregory Bateson at Tarrytown, New York, four years later: ‘After Robert Moses, What?: an exploration of new ways of governing cities and institutions’.

After Robert Moses, What?

An exploration of new ways of governing cities and institutions,November 1974, at Tarrytown, New York

Simon Sadler

Robert Moses’ legacy was a spectre haunting discussion at the New York Wenner-Gren symposium in 1970. The opportunity for Bateson and Jaque Robertson to continue that discussion came four years later, when the Tarrytown Conference Center (a converted Gilded Age Hudson Valley estate which had been a favorite weekend retreat for Margaret Mead’s circle) invited them to serve as panelists at the first in its series of ‘learning and leisure’ weekends. “After Robert Moses, What?” asked the 1974 launch event, promising “an exploration of new ways of governing cities and institutions”. The conversation was shaped by the publication of The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, the epic study of New York’s politics and urban development, whose author Robert Caro attended the event as a panelist. Another panelist, the prominent architectural critic Peter Blake—formerly Curator of the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and formerly editor of Architectural Forum—had that September published a broadside op-ed against modern architecture in The Atlantic, ‘The Folly of Modern Architecture’. Robertson, Bateson, Caro and Blake were joined as Tarrytown panelists by The Village Voice city editor and Moses nemesis Mary Nichols, and George Sternlieb, founder of the Center for Urban Policy Research at Rutgers University.

Billed as an anthropologist, ecologist and expert on change, Bateson’s role on a panel of urbanists was ostensibly the most surprising. Still more unexpected was his decision to concentrate on Caro’s theme of power. Outside of emergencies, “the concentration of political power which enabled Robert Moses, the ‘Power Broker’, to act effectively, is today a sociologically and psychologically obsolete phenomenon”, Bateson reckoned. So, “how can large scale decisions of the scale of city planning and upward be reached and implemented?”1 Urbanism thus presented Bateson with the opportunity for “a

reexamination of the basic premises of political science in the light of cybernetics”. Power was a “metaphor” for “patterns of interaction in real time” within more complex urban ecosystems, constituted by the passing-on of information, the distribution of rewards and punishments, the shaping “of taste—rage—amusement”, “of contexts, punctuation, etc.”, and the modulation “of the flow of goods and services”. Systemically, “the individual who is in a crucial position in the system is a part of that system and is therefore subject to all the constraints and necessities of the particular part-whole relationship in which he exists. The part can ‘control’ the whole only up to a formal logical level.” In which case, individual power was not just metaphorical, but mythical, “a player in a drama … reinforced by applause, prestige, etc. … the endless and insatiable hunger for this validation … creates a runaway … But the actor has only a part in the play; the tiger is only a part of the forest.” This analysis continued Bateson’s battle against vulgar mechanistic understandings of the world, which rejected any understanding of power as principally physical. As an evolutionary model of politics, it was also anti-Spencerian, founded instead on ecological balance: “All mammalian needs are for optima. An optimum amount of protein, oxygen, sex, warmth, entertainment, water, air, etc., is what is ‘good’. And all these goods become toxic beyond the optimum. If some X is good, then more X is not necessarily better … The metaphor of power derived from physics or engineering suggests that more power will always be more powerful. But this is an anti-biological, anti-ecological view of the matter—an untrue view”.

Convinced that humans are motivated not just by the pursuit of power, but by fear, hate, love, threats, pain avoidance, and the rest, Bateson was, Philip Guddemi believes, “a values pluralist”. David Graeber and David Wengrow’s revisionist 2023 anthropology The Dawn of Everything: a new history of humanity, which draws on Bateson, similarly cautions against reductionist models of human societies, preferring to foreground political possibility. But even Bateson seemed stumped at Tarrytown by the political implications of his framework: “having thrown away our only conventional tool for thinking about ‘power’—what next? In other words, the social changes which give rise to our conference—that change from the possibility of people like R. Moses to the impossibility of such people or roles”. If future urban change was to be collective, Bateson makes no mention of class, race, or gender, and Bateson was wary of radicalism as a mode of dissensus, conflict,or in ecological terms, schismogenesis.2 At Wenner-Gren in 1970, Bateson had allowed discussion to focus on heterarchic governance; by Tarrytown he seems to have forgotten about this prospect.

Instead, Bateson’s position paper for Tarrytown fell into the hands of Stewart Brand, who shared it with readers of CoEvolution Quarterly, his eco-cybernetic talking shop for the countercultural bible that was the Whole Earth Catalog, of which he was founder-editor. Famously anticipating the convergence of countercultural cybernetics with deregulation, information technology, and expanded, decentralised electronic communications, Brand doubtless hoped to pass Moses’s broken power to citizen networks for redistribution and reassembly; later in the 70s, Tarrytown Conference Center and its offshoots offered crash-courses in entrepreneurship and computing, attracting counterculturalists on the one hand, corporate executives on the other. It seems safe to say, however, that Bateson would be more sympathetic with the avowedly ‘pluriversal’ and ‘decolonial’ expositions of anthropology and human ecology expounded by Graeber and Wengrow than with the tech libertarianism and neoliberalism nascent in Brand’s circle. “Money is certainly anti-ecologic”, Bateson said at Tarrytown, because surely, money is reductive as a conveyor of information—another metaphor perhaps, in Bateson’s logic.

Much as Bateson breached conventional science with a grand interactive ecology of communication, system, feedback, perception, feeling and consciousness, so too he hoped to breach conventional political science. The fallacy of divide-and-rule urban politics ravages an urban ecology of mind. Jaque Robertson had heard the call. In anticipation of the upcoming Tarrytown event, Robertson wrote to Bateson that, through “numerous rereadings of Steps … you have been with me these last few years … you have changed my perception both of the world-around-me and myself-within-that-world.” In a lecture series on architecture and planning he delivered at Harvard’s Salzburg Seminar, Robertson admitted, Bateson “was (willingly or not) the central spectre. I have become, I suspect,

architecture’s leading neo-Batesonian”. In accordance with Bateson’s taste for eclectic reading, Robertson shared reading recommendations drawn not from his deep expertise in architecture and planning, but from literature and criticism—novelist John Fowles, and critic George Steiner Steiner, “one of the few men of literature who seem to have a pretty good knowledge of the history of science—which of course brings him closer to that kind of Biblical wholeness of view to which you refer so often.” From one spectre to another: for Robertson, what came after Robert Moses was Gregory Bateson.

The effects of Councious Purpose on Human Adaptation

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec iaculis nisi in gravida tristique. Nulla lacinia diam vitae odio tincidunt, eu semper nisi fermentum. Pellentesque hendrerit, orci vitae aliquam tempus, lectus sem sagittis urna, volutpat vehicula ligula risus aliquam turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec id tellus nec nisi aliquet condimentum. Nam sed ex volutpat, pharetra purus at, ullamcorper nisl. Proin rutrum id arcu non dictum. Proin id lobortis dolor. Vestibulum non rutrum ex, ac pellentesque eros. Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Nulla ut sagittis justo. Morbi est lectus, tempor nec commodo at, posuere nec neque. Praesent egestas efficitur interdum. Donec ullamcorper porttitor purus, sit amet vulputate sapien pulvinar non. Nunc malesuada ipsum elit, id pellentesque tellus convallis eget. Cras vitae mauris eget quam hendrerit volutpat.

Maecenas sed augue sem. Fusce sodales sed velit non lacinia. Phasellus quam quam, facilisis ac gravida nec, dapibus a metus. Duis dignissim augue in augue ullamcorper convallis. Suspendisse vulputate lacus tortor, sed elementum est fermentum nec. Duis a libero semper, tincidunt mauris nec, maximus erat. Nunc et tortor vulputate, feugiat mi quis, eleifend neque. In vel nunc vitae magna posuere viverra id id lectus. Integer dapibus pretium fermentum. Nulla eget magna tempus, consectetur risus nec, pharetra nulla.

Phasellus quis lorem ac dui fermentum luctus. Nullam id ipsum ipsum. Duis maximus purus sed massa mollis condimentum. Curabitur faucibus at nibh ut cursus. Curabitur quis quam placerat, pulvinar sapien a, mattis dolor. Integer sit amet rhoncus nisi. Cras cursus nulla vel mattis feugiat. Aenean vulputate accumsan eros eget lacinia. Donec in turpis et dolor luctus fringilla ac et purus. Integer condimentum ante sed ex lobortis, quis ornare sapien ultricies. Pellentesque commodo vestibulum mi vitae lobortis. Duis gravida, ipsum sit amet congue rutrum, nunc est consectetur urna, at congue quam urna suscipit risus. Duis a hendrerit nisl.

Nulla facilisi. Etiam ac nibh id arcu pretium egestas. Donec suscipit nulla quis eleifend volutpat. Morbi tempor ullamcorper purus, et laoreet diam maximus vitae. In eleifend tortor eget elit tincidunt, vitae egestas ante consequat. Nam imperdiet augue ut elit cursus laoreet. Proin sit amet augue ac augue cursus accumsan. Cras at tincidunt diam, a semper quam. Phasellus quis ornare massa, ac convallis ante. Nam interdum viverra lorem, in tincidunt massa vulputate sit amet. Quisque efficitur pretium ligula, non mattis risus blandit vitae. Mauris sodales justo a est gravida, non scelerisque justo tincidunt.

Mauris ut ligula scelerisque tortor sodales interdum non vitae turpis. Praesent feugiat lectus molestie elementum congue. Etiam consectetur sodales urna dignissim dictum. Ut tempor facilisis justo, vel faucibus turpis pulvinar vitae. Integer at posuere magna. Aenean euismod est in tincidunt scelerisque. In sit amet massa eu libero volutpat condimentum. In at orci nibh. Sed in risus magna. Donec et interdum nisi. Pellentesque condimentum lectus quis metus porta venenatis. Nulla gravida nibh in nisi fringilla sodales. Donec pulvinar tortor turpis, quis cursus velit molestie varius. Curabitur sem velit, volutpat auctor venenatis ac, dictum non lorem. Vestibulum a enim sodales, vehicula diam non, commodo risus. Aenean eu elementum enim.

The effects of Councious Purpose on Human Adaptation

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec iaculis nisi in gravida tristique. Nulla lacinia diam vitae odio tincidunt, eu semper nisi fermentum. Pellentesque hendrerit, orci vitae aliquam tempus, lectus sem sagittis urna, volutpat vehicula ligula risus aliquam turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec id tellus nec nisi aliquet condimentum. Nam sed ex volutpat, pharetra purus at, ullamcorper nisl. Proin rutrum id arcu non dictum. Proin id lobortis dolor. Vestibulum non rutrum ex, ac pellentesque eros. Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Nulla ut sagittis justo. Morbi est lectus, tempor nec commodo at, posuere nec neque. Praesent egestas efficitur interdum. Donec ullamcorper porttitor purus, sit amet vulputate sapien pulvinar non. Nunc malesuada ipsum elit, id pellentesque tellus convallis eget. Cras vitae mauris eget quam hendrerit volutpat.

Maecenas sed augue sem. Fusce sodales sed velit non lacinia. Phasellus quam quam, facilisis ac gravida nec, dapibus a metus. Duis dignissim augue in augue ullamcorper convallis. Suspendisse vulputate lacus tortor, sed elementum est fermentum nec. Duis a libero semper, tincidunt mauris nec, maximus erat. Nunc et tortor vulputate, feugiat mi quis, eleifend neque. In vel nunc vitae magna posuere viverra id id lectus. Integer dapibus pretium fermentum. Nulla eget magna tempus, consectetur risus nec, pharetra nulla.

Phasellus quis lorem ac dui fermentum luctus. Nullam id ipsum ipsum. Duis maximus purus sed massa mollis condimentum. Curabitur faucibus at nibh ut cursus. Curabitur quis quam placerat, pulvinar sapien a, mattis dolor. Integer sit amet rhoncus nisi. Cras cursus nulla vel mattis feugiat. Aenean vulputate accumsan eros eget lacinia. Donec in turpis et dolor luctus fringilla ac et purus. Integer condimentum ante sed ex lobortis, quis ornare sapien ultricies. Pellentesque commodo vestibulum mi vitae lobortis. Duis gravida, ipsum sit amet congue rutrum, nunc est consectetur urna, at congue quam urna suscipit risus. Duis a hendrerit nisl.

Nulla facilisi. Etiam ac nibh id arcu pretium egestas. Donec suscipit nulla quis eleifend volutpat. Morbi tempor ullamcorper purus, et laoreet diam maximus vitae. In eleifend tortor eget elit tincidunt, vitae egestas ante consequat. Nam imperdiet augue ut elit cursus laoreet. Proin sit amet augue ac augue cursus accumsan. Cras at tincidunt diam, a semper quam. Phasellus quis ornare massa, ac convallis ante. Nam interdum viverra lorem, in tincidunt massa vulputate sit amet. Quisque efficitur pretium ligula, non mattis risus blandit vitae. Mauris sodales justo a est gravida, non scelerisque justo tincidunt.

Mauris ut ligula scelerisque tortor sodales interdum non vitae turpis. Praesent feugiat lectus molestie elementum congue. Etiam consectetur sodales urna dignissim dictum. Ut tempor facilisis justo, vel faucibus turpis pulvinar vitae. Integer at posuere magna. Aenean euismod est in tincidunt scelerisque. In sit amet massa eu libero volutpat condimentum. In at orci nibh. Sed in risus magna. Donec et interdum nisi. Pellentesque condimentum lectus quis metus porta venenatis. Nulla gravida nibh in nisi fringilla sodales. Donec pulvinar tortor turpis, quis cursus velit molestie varius. Curabitur sem velit, volutpat auctor venenatis ac, dictum non lorem. Vestibulum a enim sodales, vehicula diam non, commodo risus. Aenean eu elementum enim.

The effects of Councious Purpose on Human Adaptation

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec iaculis nisi in gravida tristique. Nulla lacinia diam vitae odio tincidunt, eu semper nisi fermentum. Pellentesque hendrerit, orci vitae aliquam tempus, lectus sem sagittis urna, volutpat vehicula ligula risus aliquam turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec id tellus nec nisi aliquet condimentum. Nam sed ex volutpat, pharetra purus at, ullamcorper nisl. Proin rutrum id arcu non dictum. Proin id lobortis dolor. Vestibulum non rutrum ex, ac pellentesque eros. Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Nulla ut sagittis justo. Morbi est lectus, tempor nec commodo at, posuere nec neque. Praesent egestas efficitur interdum. Donec ullamcorper porttitor purus, sit amet vulputate sapien pulvinar non. Nunc malesuada ipsum elit, id pellentesque tellus convallis eget. Cras vitae mauris eget quam hendrerit volutpat.

Maecenas sed augue sem. Fusce sodales sed velit non lacinia. Phasellus quam quam, facilisis ac gravida nec, dapibus a metus. Duis dignissim augue in augue ullamcorper convallis. Suspendisse vulputate lacus tortor, sed elementum est fermentum nec. Duis a libero semper, tincidunt mauris nec, maximus erat. Nunc et tortor vulputate, feugiat mi quis, eleifend neque. In vel nunc vitae magna posuere viverra id id lectus. Integer dapibus pretium fermentum. Nulla eget magna tempus, consectetur risus nec, pharetra nulla.

Phasellus quis lorem ac dui fermentum luctus. Nullam id ipsum ipsum. Duis maximus purus sed massa mollis condimentum. Curabitur faucibus at nibh ut cursus. Curabitur quis quam placerat, pulvinar sapien a, mattis dolor. Integer sit amet rhoncus nisi. Cras cursus nulla vel mattis feugiat. Aenean vulputate accumsan eros eget lacinia. Donec in turpis et dolor luctus fringilla ac et purus. Integer condimentum ante sed ex lobortis, quis ornare sapien ultricies. Pellentesque commodo vestibulum mi vitae lobortis. Duis gravida, ipsum sit amet congue rutrum, nunc est consectetur urna, at congue quam urna suscipit risus. Duis a hendrerit nisl.

Nulla facilisi. Etiam ac nibh id arcu pretium egestas. Donec suscipit nulla quis eleifend volutpat. Morbi tempor ullamcorper purus, et laoreet diam maximus vitae. In eleifend tortor eget elit tincidunt, vitae egestas ante consequat. Nam imperdiet augue ut elit cursus laoreet. Proin sit amet augue ac augue cursus accumsan. Cras at tincidunt diam, a semper quam. Phasellus quis ornare massa, ac convallis ante. Nam interdum viverra lorem, in tincidunt massa vulputate sit amet. Quisque efficitur pretium ligula, non mattis risus blandit vitae. Mauris sodales justo a est gravida, non scelerisque justo tincidunt.

Mauris ut ligula scelerisque tortor sodales interdum non vitae turpis. Praesent feugiat lectus molestie elementum congue. Etiam consectetur sodales urna dignissim dictum. Ut tempor facilisis justo, vel faucibus turpis pulvinar vitae. Integer at posuere magna. Aenean euismod est in tincidunt scelerisque. In sit amet massa eu libero volutpat condimentum. In at orci nibh. Sed in risus magna. Donec et interdum nisi. Pellentesque condimentum lectus quis metus porta venenatis. Nulla gravida nibh in nisi fringilla sodales. Donec pulvinar tortor turpis, quis cursus velit molestie varius. Curabitur sem velit, volutpat auctor venenatis ac, dictum non lorem. Vestibulum a enim sodales, vehicula diam non, commodo risus. Aenean eu elementum enim.