About

the research

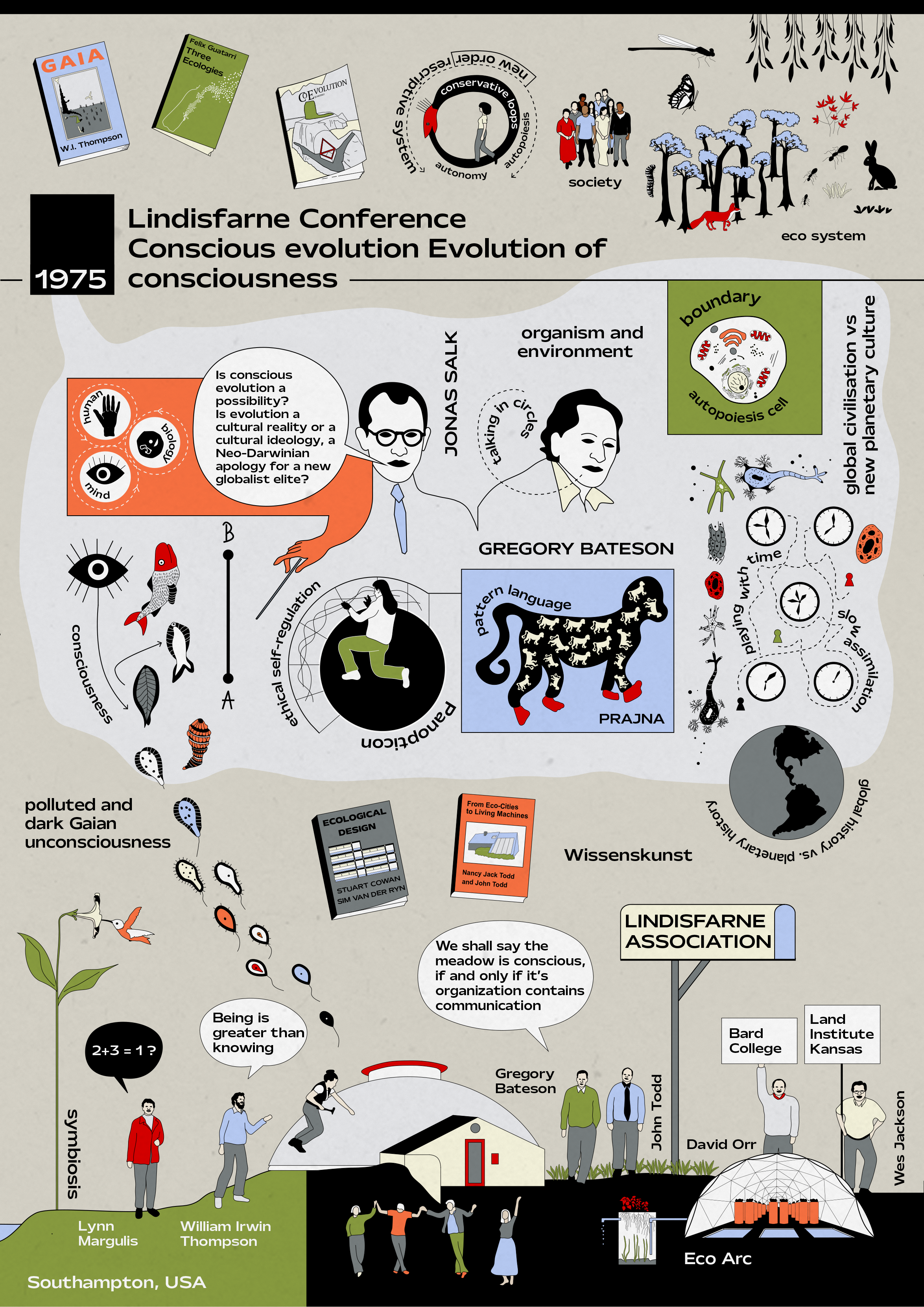

Bateson's Cosmos

Here you can explore the outcomes of Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec iaculis nisi in gravida tristique. Nulla lacinia diam vitae odio tincidunt, eu semper nisi fermentum.

Steps Around a Theory of Action: Notes on Seven Bateson Conferences

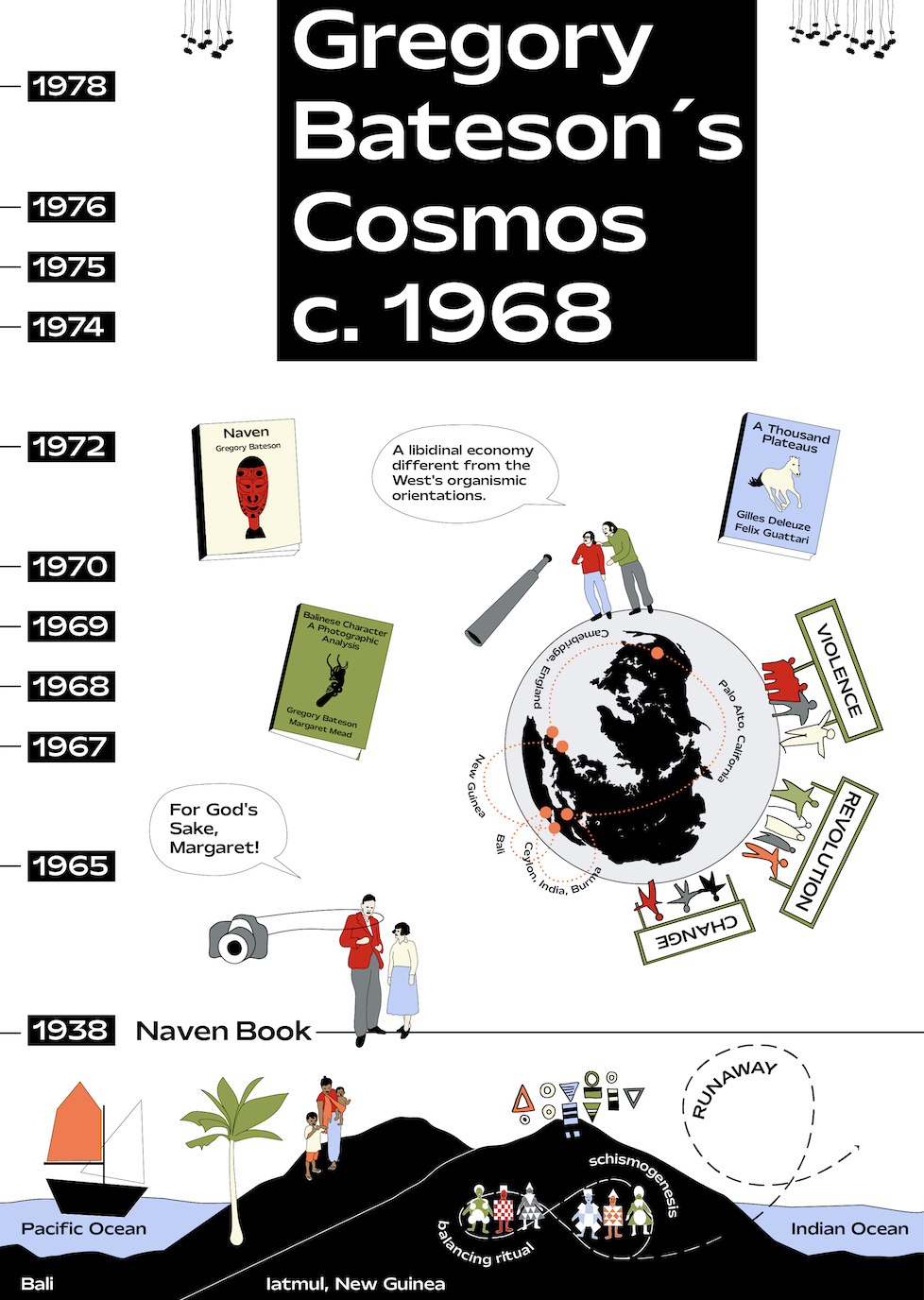

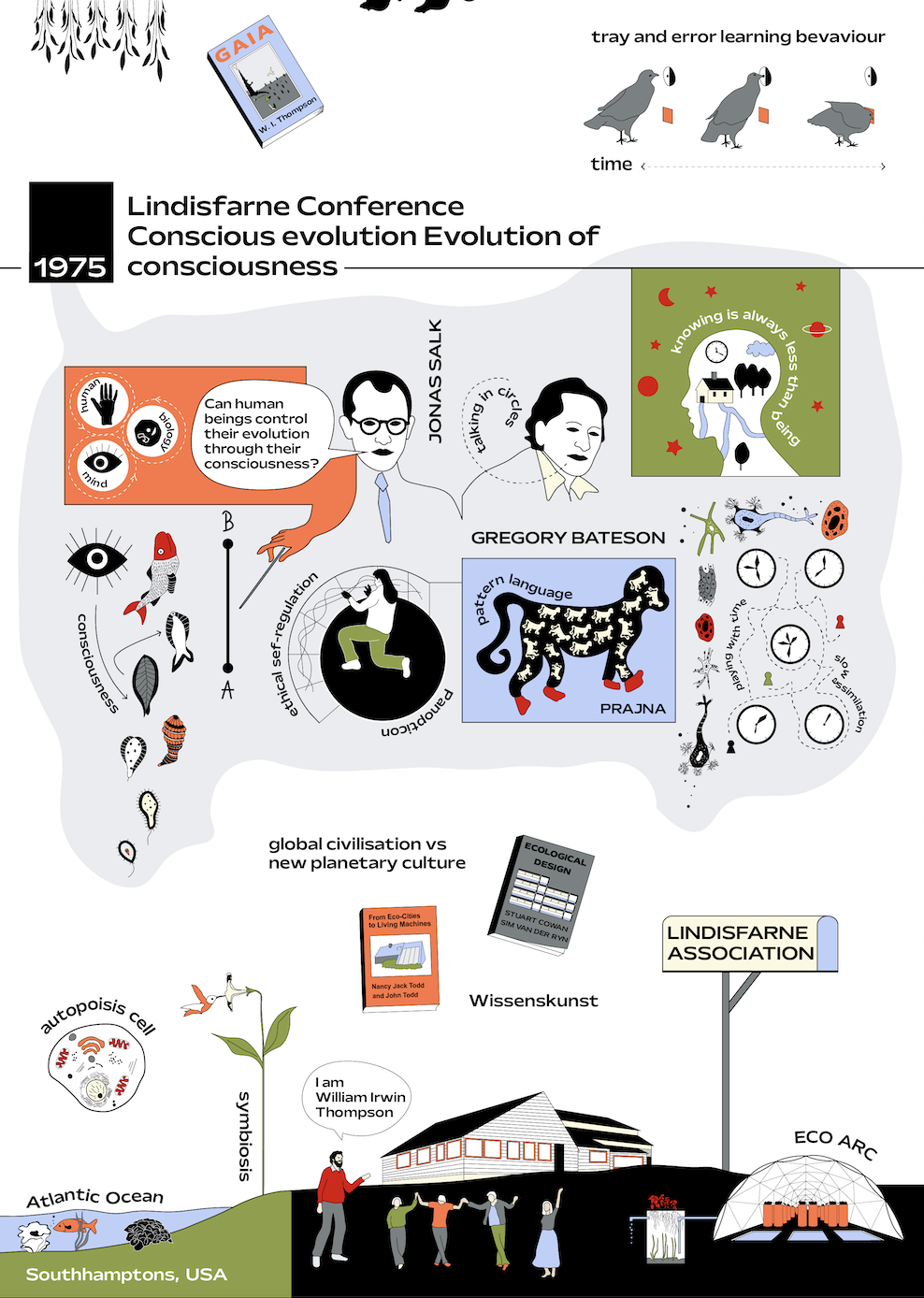

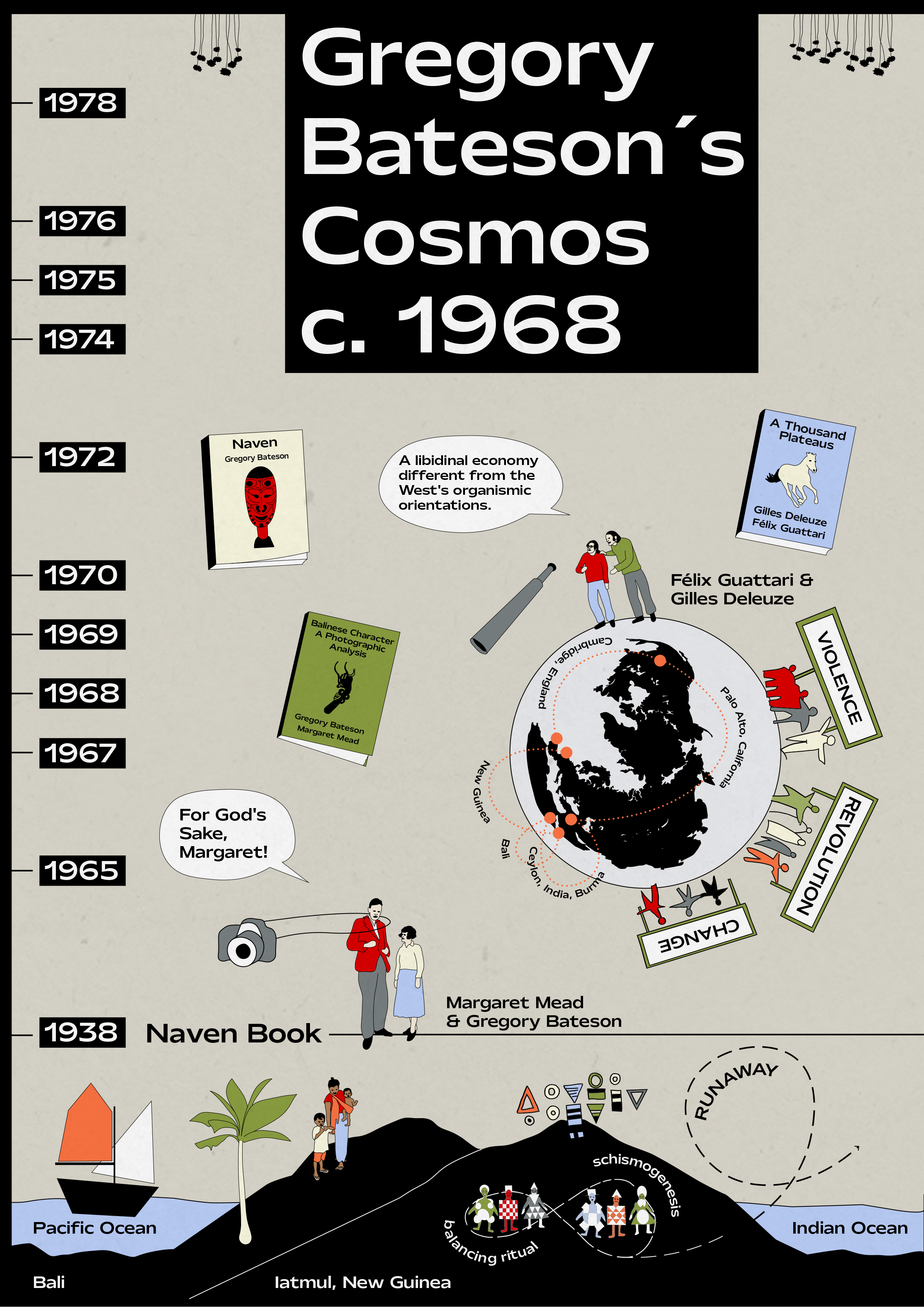

Steps Around a Theory of Action is a collection of short introductions to a series of conferences, some well-known and others hitherto unexplored, in which Gregory Bateson addressed questions related to action within the ecological crisis. The series of short texts on the conferences and the graphic titled Bateson’s Cosmos draw heavily from many primary sources, including transcripts, letters, reports, and audio and video recordings in multiple archives.

Several things prompted me to invite the others to write these short texts and develop Bateson’s Cosmos. The first was a comment from a reviewer of the project proposal who mentioned that the project had the potential to open up Bateson’s archive in ways that could help think beyond the contemporary crisis of imagination affecting many practices and practitioners, who are attempting to navigate the incommensurable space between the violent unmaking and making of ecological systems. The second was my previous experience of trying to teach Bateson’s ideas to students, mainly from design disciplines, who found it difficult to understand the richness of Bateson’s somewhat transdisciplinary and abstract writings, partly because they were unable to grasp the specific historical, geographical and intellectual contexts in which they emerged. The third was a short exercise led by Jon Goodbun at the Santa Cruz Diner during the archival visit in September 2023. Jon prompted team members to draw two lines. The first line was to indicate Bateson’s movement across different landscapes. The second line was to depict the movement of one’s own interests in ecology and design. These lines prompted us to consider how Bateson’s thought developed as he moved through different contexts. It also helped us to reflect on our own connection to these changing ideas. At this workshop, I produced a sketch containing the vague outlines of Bateson’s Cosmos.

During my brief time at the archive, I glimpsed how these conferences allowed one to see Bateson’s ideas in the specific context of the networks of sites, people and objects that inspired Bateson’s thinking and in which his ideas were embodied and critiqued. Moreover, the records of these events are lively, conversational, and playful, which are aspects of his work that are often less visible in his published monographs.

As we started to work with the material related to the conferences, the four members of the archive group, Jon Goodbun, Simon Sadler, Ben Sweeting and myself, had different levels of previous experience with Bateson’s work, as well as different research interests and questions, all of which influenced our individual ways of narrating the events. These differences carry through in the voice and style of the texts that I have explicitly preserved as a way of maintaining the “multiple descriptions,” which, as Bateson reminds us, are crucial to an ecological understanding. In addition, it was apparent that the stories we wanted to tell could not be conveyed with words alone. Nor did we see our task as merely about storytelling. Rather, we aimed to make the story available in a way that allowed readers to find their own ways of interacting with it and to develop their own trajectories of interest. As such, based on the textual summaries provided by the rest of the group and with further consultations of the archival material, I expanded the drawing Bateson’s Cosmos into an interactive resource . This drawing, which I hand sketched, was then redrawn digitally by Leonie Link and Florian Tudzierez, and later converted into an interactive resource with the help of Paola Ferrari and Stefanie Huthoefer. I am particularly grateful to the Weimar team for their contributions and feedback which helped to develop the drawing.

Bateson’s career moved between numerous contexts, including anthropology, psychiatry, and cybernetics (the transdisciplinary study of feedback). What was common throughout Bateson’s work was the exploration of living systems in terms of communication and learning, rather than matter and energy. [1] For Bateson, these contexts all participate in the same sets of ecological relationships, and it is the human tendency (often well intentioned) to address them separately that lies at the root of the ecological crisis. Engaging with the archive, both as a group and as individuals, it became immediately clear that Bateson’s post-’67 work was relevant to the questions of (design) action that prefigured our research project. This was by no means the only period in which ideas about action appeared in his work. However, there are conditions specific to this conjuncture that influenced the nature of Bateson’s exploration, such as the surging interest in both the ecological crisis and cybernetics, as some of us have argued in earlier work.[2] For example, during this period Bateson became directly involved in environmental projects and discussions through his work as a member of the Ecology and Man Committee at the University of Hawaii (1965-1972). He sought to address the question of action in a systematic way as evidenced by his interest in developing “a theory of action,” and his search for an “applied epistemology” that was ecological in orientation.[3]

In our work, we show how Bateson’s contributions to the Dialectics of Liberation Congress in 1967 reveal his concerns about particular kinds of action driven by “conscious purpose,” as well as how subsequent conferences show glimpses of Bateson’s efforts to work with practitioners (including architects and designers) who were trying to develop alternatives. Each of us reads the ’67 moment and what followed in Bateson’s praxis differently. For example, Jon Goodbun understands it as a turn towards wise-action. Dulmini Perera sees it as the emergence of a particular kind of an organic intellectual praxis for reflecting on the violence of techno-environmental practices. Simon Sadler sees an ecological politics. While Ben Sweeting perceives it as a move away from systems approaches driven by conscious purpose. Despite these diverse readings, we collectively make a case as to why this moment is worthy of the attention of anyone interested in understanding how Bateson’s work contributes to thinking about design action.

Through the conference events, we can begin to see how Bateson’s concept of “mind” helped practitioners to think beyond problematic dualisms such as ideas vs action, pattern vs matter, or idealism vs materialism. Taken together, the image of Bateson’s Cosmos, and the accounts of the conference narratives help to evoke what Bateson would in the Princeton 1969 conference call the “territory of minds.”[4] The notion of a territory of minds suggested that the broader crisis of ideas and imagination were enfolded into systems spread across biological, neurological, environmental, technical systems not limited to the brain. A territory of minds involves thinking about “dynamic ‘circuits’ of mental process which incorporate (but aren’t necessarily separable into) brains, bodies, soil, air, tools, and so on.” [5] Various environmental practices, including architecture and design, as well as the habits and tools of their practitioners, all form a significant part of these territories, as the image of Bateson’s Cosmos suggests.

The networks of sites, objects, and people that formed Bateson’s cosmos also suggest an alternative history of post-WWII cybernetics, one which radically differs from the better-known histories that relate cybernetics to military-industrial logics, global techno-environmental managerialism and the countercultural origins of Silicon Valley liberalism. This alternative history of ecological cybernetics contains unfinished prototypes, germinal ideas about what technology, information and design should be, as well as open-ended conversations about ecology, action, violence and open systems that prefigure many contemporary concerns about how to act within the present ecological crisis.

I sincerely hope the readers will find in this resource both an invitation as well as a prompt to further explore Gregory Bateson’s work.

Living systems would include octopuses, cities, families, institutions, ecosystems.

Dulmini Perera, “Architectures of Coevolution: Second-order Cybernetics and Architectural Theories of the Environment c. 1959-2013” (PhD diss., University of Hong Kong, 2017); Jon Goodbun, “The Architecture of the Extended Mind: Towards a Critical Urban Ecology”. (PhD diss., University of Westminster School of Architecture and the Built Environment, 2011); Simon Sadler, “An Architecture of the Whole,” Journal of Architectural Education 61, no. 4 (2008): 108–29, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40480872.

Gregory Bateson. “The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation.” Conference memo enclosed with letter dated November 5, 1968, Box 39, Binder 4, Document B4-6dGregory Bateson Papers. UCSC Special Collections and Archives. Underlining original. An abridged version of the memo is published in A Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind, ed. Rodney E. Donaldson (Triarchy Press, 2023). Jon Goodbun has brought attention to the significance of Bateson’s concern with a theory of action within this often-overlooked text. Jon Goodbun, “Gregory Bateson and the Political” (unpublished manuscript, November 2025). Dulmini Perera, Jon Goodbun, Phillip Guddemi, and Fred Turner, “Gregory Bateson and the Political,” Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design, RSD11. Article 015. https://rsdsymposium.org/gregory-bateson-and-the-political/

See this term discussed by Ben Sweeting, “Wenner-Gren conference on the Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” (in this output).

See “applied epistemology” discussed in Mary Catherine Bateson, Our Own Metaphor: A Personal Account of a Conference on the Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation (Hampton Press, 1972), 147-220.

See this term discussed by Dulmini Perera, “Conference on Human Distress and Rapid Social Change,” (in this output)

Phillip Guddemi, e-mail message to author, January 08, 2025.

Acknowledgement

Steps Around a Theory of Action was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – grant number 508363000 and Arts and Humanities Research Council [grant number AH/X002535/1].

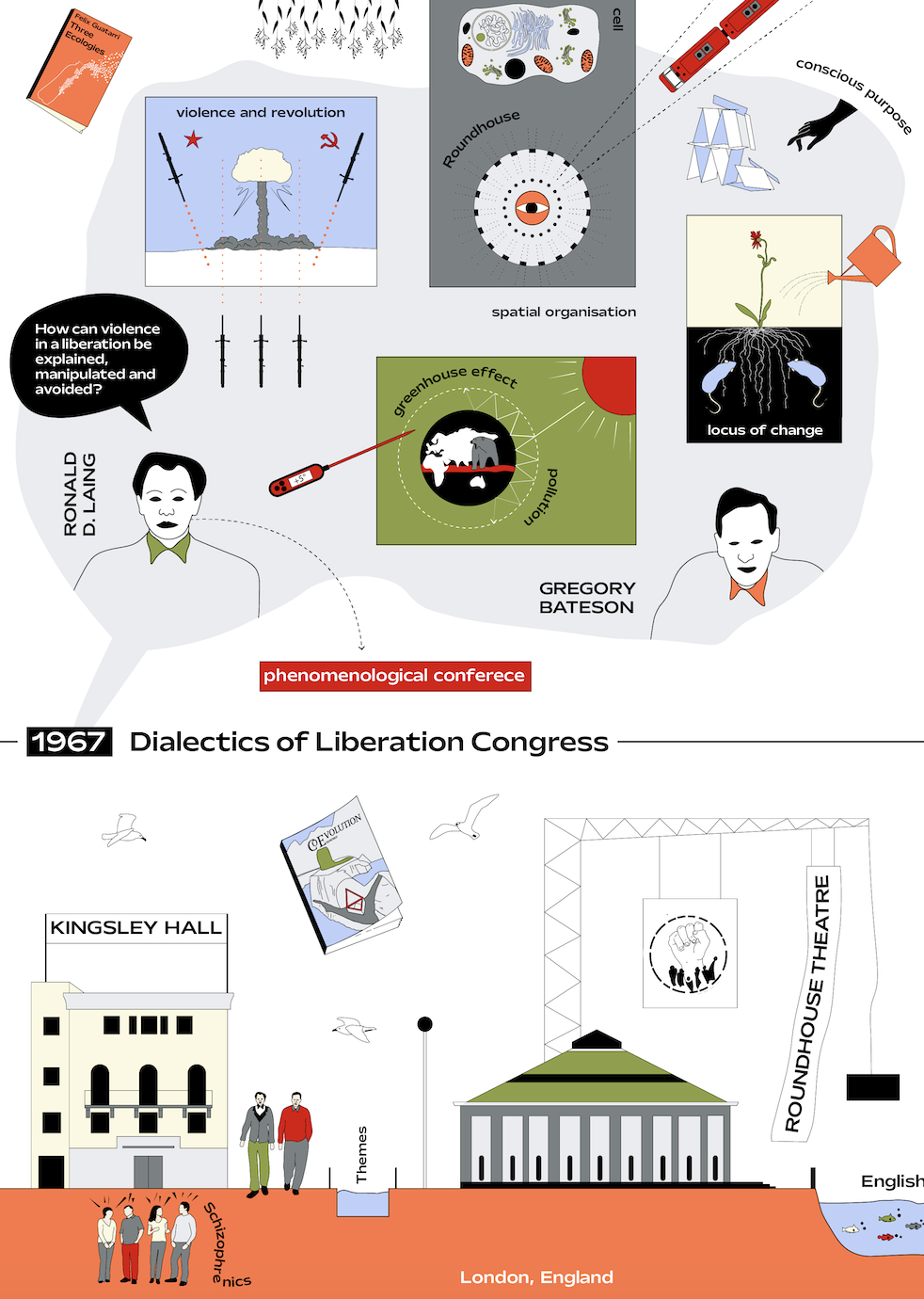

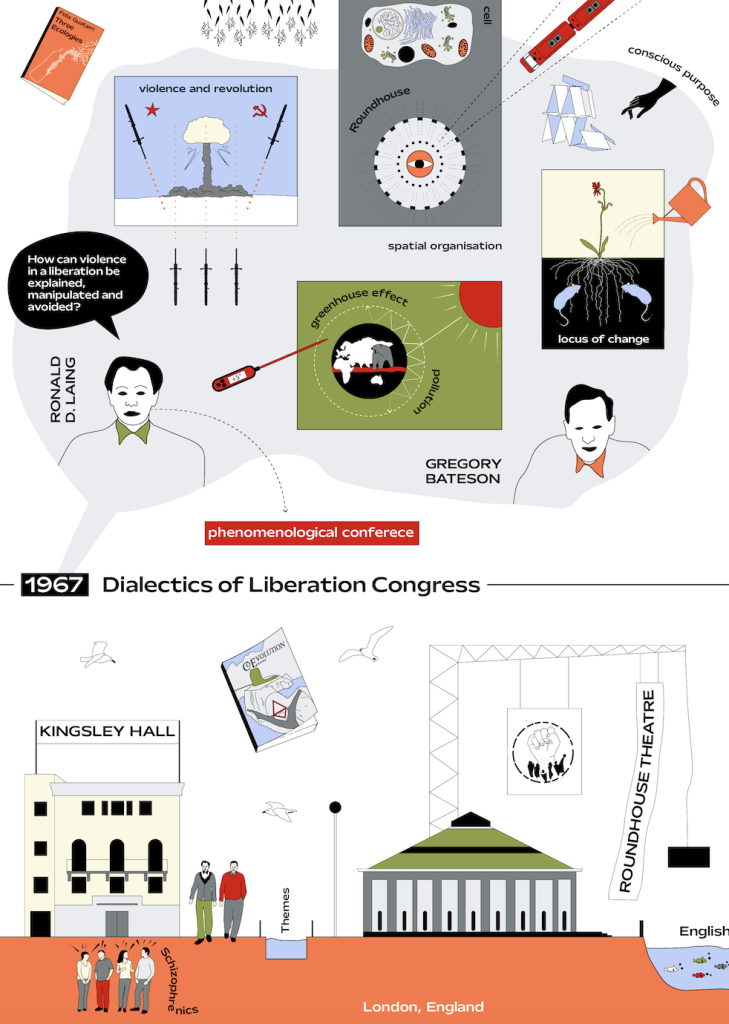

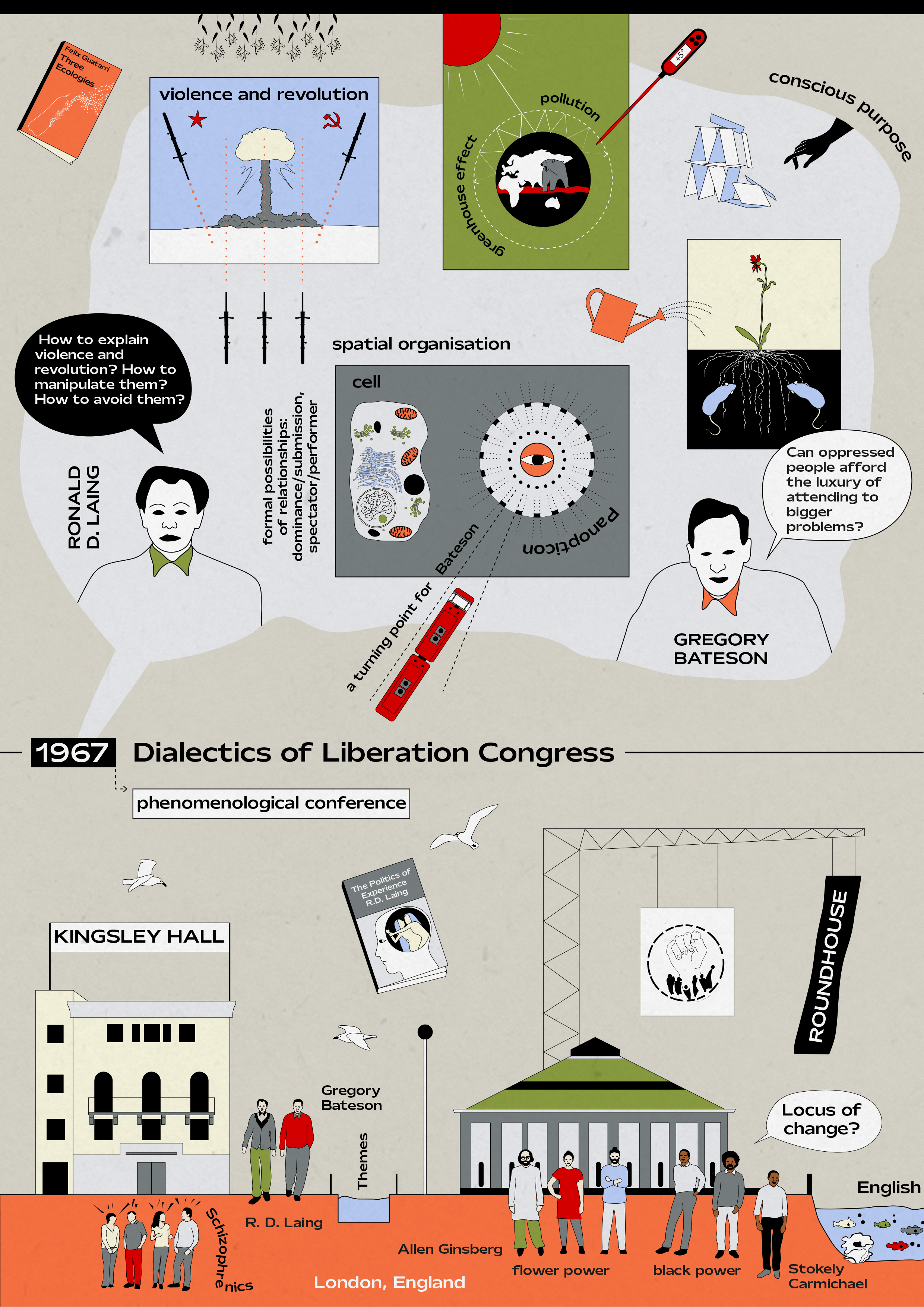

In July 1966 Gregory Bateson received a letter from Dr Ronnie D Laing, telling him that, together with David Cooper, he had established the Institute of Phenomenological Studies in London, and outlining plans for a conference to be held there the following summer of 67. They invited Bateson to participate, promising an experimental format and opportunities for informal dialogue.

The event—The Dialectics of Liberation Congress—would arguably prove to be one of the most significant turning points in the already nomadic trajectory of this significant thinker.[1]

Bateson had first met Laing in the early 60s, while Bateson was still at the VA Hospital in Palo Alto, and Laing was based at the Tavistock Institute of Social Relations in London. There had been some correspondence between Laing and the Bateson Group regarding the possible sharing of research materials, first initiated by Don Jackson in Bateson’s team, with Laing then visiting Bateson at Palo Alto in September 1962. Later that year, Bateson wrote an enthusiastic letter of support for Laing and his work, suggesting that what Laing described as his “phenomenological approach,” was “at the present time one which holds out good promise of achieving the wider view which we need.”[2]

This approach that Laing developed was sometimes described as an “existential phenomenology,” or a “phenomenological psychology,” and has widely been interpreted as, if not exactly a synthesis, then at least a “scratching together” of the work of Bateson with various strands of existential, post-colonial, Marxian, feminist and new left thought. Importantly, we should remember that the so-called Paris Manuscripts, written in 1844 by the twenty-six year young Karl Marx, with their rich and suggestive “Young Hegelian” theories of alienation and perception, were only translated into English in 1956 and French in 1962,[3] and soon inspired exciting new readings of existential and phenomenological Marxisms by thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Herbert Marcuse.

In particular, Laing was very interested in the Bateson Group’s post-war double-bind theory of schizophrenia, which had argued that patients diagnosed as schizophrenic were internalising and re-presenting contradictions and double-binds that they repeatedly experienced in their external communicational and behavioural relationships with their immediate families. Thus, rather than locating the cause of a “disease” called “schizophrenia” within a diagnosed “individual” and their “mad” and damaged brain, Bateson argued that schizophrenic symptoms and behaviours are the necessary social product of particular kinds of contradictory social and communicational networks. Bateson’s thesis influenced Laing’s anti-psychiatry practice significantly, and as Laing’s biography for the Congress noted, he had, as “a founder member and Chairman of the Philadelphia Association Ltd., London, established three communities in London where people diagnosed as schizophrenic and others live in households which are entirely non-institutional settings.”[4]

In The Politics of Experience, a collection of essays written over the previous five years and also published in 1967, Laing—in parallel with some very similar moves that the French philosopher and therapist-activist pair Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari were also making at the same time, and with the same Bateson material—radically extended and amplified the wider thesis within the Bateson Group’s work: it isn’t just families that are producing schizophrenic behaviour in their members through contradictory communications and pathological relationships, they emphasised, it is our entire contemporary western, capitalist, colonial, patriarchal society.

It was on such a foundation that the Dialectics of Liberation Congress was broadly based: “our civilisation…is one of the things that is on the block here,” Bateson noted in his introduction.[5] It became an event with some significant legacy, even now within the local histories and mythologies of the London alt-left. The Congress constituted one of a series of moments of a particular conjuncture that was in play at that time, in the temporary coming-into-unstable-alignment of two broadly antiestablishmentarian groups which characterised both the audience and the speakers: the more Marxian and politically revolutionary New Left broadly conceived (including theorists Herbert Marcuse and Ernest Mandel, as well as Stokely Carmichel of the Black Panthers); and the counterculture, with its more hippy promise of social change through personal growth and transformation (represented perhaps by poet Allen Ginsberg, and maybe Gregory Bateson).

The event was held at the Roundhouse, an old disused railway locomotive turning shed, just north of where Frederick Engels had lived on Primrose Hill, and down the tracks from Camden Road Station. The round building with its inner ring of ironwork columns was like a secular church. Originally built as a turning shed for trains, it had fulfilled this purpose for some years before taking on a much more liminal “situationist” condition, becoming a space of shifting and undefined uses, purposeless yet still a significant urban form and space in North London, playing host to all kinds of events, occupations, squats, concerts and the like for decades. It was an unlikely but perhaps appropriate location for Bateson not only to launch what I have elsewhere described as his “three ecologies” period,[6] but also to present his emerging concerns regarding the possibility of acting with “wisdom” in relation to adaptation, design, and planning in the context of ecological crisis. Perhaps for some of the audience, and even Bateson himself, the Roundhouse building, in its very purposelessness—or better, its unspecified relation between form and function—provided a metaphorical or abductive structure for thinking about some of the arguments he set out.

The congress came at an interesting moment in Bateson’s career. He had finished his work at Palo Alto as an ethnologist studying patients diagnosed as schizophrenics, their families and their therapists, and the institutions that they are in, and he had moved to the Oceanic Institute on Hawaii to work with dolphins and octopuses. This might appear to be a completely disconnected field of enquiry. However, as Bateson made clear in his biography for the congress:

… schizophrenic behavior occurs when an organism is made to feel in the “wrong” regarding the basic premises of its relationship with others. But even among people, these premises are often unconscious and are in general communicated by non-verbal interaction. It therefore became relevant to study these nonverbal systems and Bateson shifted his focus of attention from the natural history of people to that of dolphins.[7]

This shift in working location and subject matter had undoubtedly also amplified Bateson’s sensitivity towards more-than-human communication in other species and ecosystems as a whole. Furthermore, Bateson arrived at the Roundhouse straight from a conference on Primitive Art and Society,[8] which had been hosted by the Wenner-Gren anthropological foundation at Burg Wartenstein in the Austrian mountains—establishing a relationship which would become a key facilitator in allowing Bateson to explore the emerging research questions that he framed at the congress in the years that followed.

Some of the themes that Bateson developed in his Primitive Art paper also fed directly into his presentation at the congress, which became one of his most audacious syntheses to that point. Bateson brought together not only two strands of his thinking, the three ecologies and our unwise consciousness, but he also sought to bring together the two components of his audience, the new left and the counterculture, through their shared concerns regarding the condition of human consciousness. The paper developed through a series of drafts and correspondence with the organisers, which he tentatively titled “Patterns, Names and Transformations.”’[9] However as the conference approached he gravitated towards the title “Consciousness Versus Nature,” before later settling on the title “Conscious Purpose Versus Nature” for the slightly reworked paper published in the book The Dialectics of Liberation[10] which David Cooper edited following the event.

In one earlier draft of the paper Bateson stated:

We think of consciousness as the great human achievement and blessing but it also makes for trouble. The human mind as a whole is itself like the oak wood, the society and the physiological body—a self-correcting, balancing system. But consciousness is a selected excerpt from this balanced whole, and the selection is guided by what we call purpose. We ignore or are unconscious of most of the mind and run after our purposes. We thus lose the wisdom of knowing ourselves as a whole.[11]

In proposing that there is a “pattern which connects” the oak forest and the real conditions of human mind and human society, Bateson is practicing what he would define in his presentation as a totemistic empathy,[12] in contradistinction to what he would, soon after, define as the “epistemological error” of a modern western cosmology—a critique which both sections of his audience could connect to.

In his presentation, Bateson repeatedly stated the paradox of consciousness—the fact that consciousness can never be aware of the totality of mind—that is to say the whole dynamic matrix of complexly patterned matter (typically biological) from which, as he argued cybernetics had shown, mind emerges. “It’s as materialistic as that” he said, surely aiming to connect with dialectical materialists (aka Marxists) in the audience. After showing that this condition or relation of consciousness to the wider ecology of mind (although he wasn’t yet calling it that) is fundamental and structurally unavoidable, he set out various questions and consequences that follow from this. Firstly, Bateson poses the question: what is it then, that makes it onto the “screen of consciousness”? How is the selection made? He answers, stating that consciousness is primarily shaped by questions of planning and purpose. He then further notes that this must be a somewhat ubiquitous condition in any conscious organisms, but this is not typically a problem, as any given organism can typically only effectively act on its immediate environment. However, in modern human societies this becomes a very serious problem and in fact constitutes the ground of our more superficial politics, for two reasons. Firstly, he suggested that, in modern western societies, consciousness was increasingly dominated by purposive goals and was, at the same time, left ever more “un-aided” by cultural forms which have the capacity to provide “systemic wisdom.” Secondly, he thought that this increasingly unwise consciousness was at the same time finding ever greater amplification beyond local contexts, and disturbing various “balances” in the bigger ecological systems, primarily through modern technologies and media.

Bateson then connected back to both strands of his audience, affirming that “it is, however, possible that the remedy for ills of conscious purpose lies with the individual.”[13] In particular, and no doubt resonating with many of the goals of the counter-culture project, Bateson wondered whether it might be possible to expand consciousness beyond the narrow constraints of purpose, and that it might be possible to “aid” consciousness towards a more systemic wisdom:

I think we should lump together dreams and the creativity of art, or the perception of art, and poetry and such things. And I would include with these the best of religion. These are all activities in which the whole individual is involved. …

We might say that in the creative art man must experience himself – his total self – as a cybernetic model.[14]

Bateson’s talk, which was the first major presentation at the congress, was followed by a significant Q&A session chaired by Laing in which some questions were further explored, as they were in a separate dialogue session that Bateson led a couple of days later with Laing, Ginsburg, and others. He repeatedly suggested to his audience that Marx was moving in the right direction, but the project remains incomplete, and is perhaps dangerous to implement unaided by a more ecological wisdom. In the Q&A, Bateson noted that “Karl Marx made a considerable contribution to the thinking that I was offering you earlier,” but warned that we needed to “look at larger systems” still.[15] And perhaps already anticipating this discussion, in a letter to Ronnie Laing in their pre-event discussions, Bateson noted that “Marx and Freud were great men but neither contributed anything that could be used for social doctrine.”[16] When asked whether oppressed peoples can afford the luxury of attending to the bigger problems that Bateson was outlining, he concluded:

It is true that there are a very large number of places in the world where what is happening to human beings shouldn’t happen to dogs. It is happening to those human beings as a result of the things that I have been talking about. There may be short-term solutions that can be reached…. But I believe the larger problem is one which it is not a luxury to attend to. I believe it is an urgent necessity to attend to the larger problems.[17]

He then gave as an example, one of the earliest references to the effects of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, giving it as an example of the unforeseen consequences of short-term human conscious purpose on bigger systems, stating that we are seeing:

The tendency to destroy his society, his total ecosystem and his own soul. There are many ways now, with the implementation of purpose, by which this can be done. It can be done by increasing CO2 in the atmosphere. CO2 is transparent to light and opaque to heat. If therefore we increase the CO2 proportion in the atmosphere, long before we start to asphyxiate, the temperature will rise. It has risen about 1 degree since 1900. A rise of 5 to 10 degrees will melt the Antarctic ice cap and the sea level will rise 200 ft. Agriculture will go out of business. Period.[18]

Bateson came out of the summer of 1967 enthused about both the emerging synthesis of his own thinking, and aware both of the timeliness of this work and its emerging audiences. But he was also aware that the potential engagement by others with his work presented new challenges. Anticipating his own concerns about the inappropriate instrumentalisation of his ideas, in a robust exchange of ideas between Bateson and Laing and Cooper in correspondence in the lead up to the event, Bateson warned the organisers that he was not completely aligned with some of their goals, and whilst he thought that their work and methods did have value in relation to the psychiatric contexts in which the ideas had evolved, these same ideas were not necessarily yet appropriate for widespread public dissemination:

I agree that the methodology of phenomenology provides a useful model for psychotherapy. But I am not sure about its being a useful model for life. There is a difference between pharmacopoeia and diet – or should be.[19]

Bateson would never again have quite the same challenging mix of engaged and politicised new left and counterculture audience that he had in London that summer. For many of the audience and several of the speakers, the route out of the Roundhouse led them straight to the struggles on the streets of 1968. It inspired the organisers of the event, Laing and Cooper, to found the perhaps even more legendary Anti-University of London the following year, pulling in other key thinkers such as Stuart Hall.[20]

Bateson did not follow his colleagues onto the streets. Instead, he headed to the ivory towers of Burg Wartenstein, as he followed up on the Wenner-Gren relationships that he established at the Primitive Art and Society conference he contributed to shortly before London, resulting in a collaboration with this anthropological funding organisation which would play a key role in the next stage of Bateson’s work, facilitating three key Wenner-Gren conference events that followed in 1968, 1969 and 1970.

(And this story, which started with Ronnie Laing adopting Bateson as some kind of a mentor and guru, will end with Stewart Brand taking up that position.)

We are all indebted of course to Anthony Chaney’s wonderful exploration and bringing to life of this event in his excellent Runaway: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Reference letter from Gregory Bateson to Mary C Ritter of the Bollingen Foundation, with a cover letter to Ronnie Laing, November 19, 1962, box 18, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Unpublished during Karl Marx’s lifetime, the notebooks were collected together and first published in Moscow in the 1930s.

Dialectics of Liberation Participant Biographies document, box 27, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Gregory Bateson, “Consciousness Versus Nature,” Dialectics of Liberation Congress transcript for July 17, 1967. Accessed January 1, 2025, https://villonfilms.ca/main/transcripts-dialectics-gregory-bateson-17-7-67.pdf

I have set out Bateson’s three ecologies period and the key papers that constitute it, in for example: Jon Goodbun, “The Two Ecologies/The Three Ecologies,” Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design RSD12 (2023). https://rsdsymposium.org/jon-goodbun-rsd12/; “How Many Ecologies?” Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design RSD11 (2022). https://rsdsymposium.org/how-many-ecologies-80/; “The Two Orders of the Three Ecologies” (unpublished manuscript, March 2025).

Gregory Bateson, biography submitted for the congress brochure, attached to letter to Laing, January 11, 1967 (dated 1966!), box 27, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Convened by Raymond Firth.

Gregory Bateson, letter to Joseph Burke, March 13, 1967, box 27, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

David Cooper, Dialectics of Liberation (Penguin, 1968). N.B. this is also the version that was published in Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Ballantine, 1972).

Gregory Bateson, “Consciousness Vs. Nature Synopsis,” July 17, 1967, box 27, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

In a more extemporised later section of his talk at the congress, Bateson noted that “one of the rather interesting things is that in several parts of the world, especially Australia, ‘primitive man’ has exercised himself very particularly about how to identify with animals; how to get an empathic feeling of what it is like.” See also my discussion of the role and potential of totemism in Bateson’s thought in several recent and forthcoming papers, including Goodbun, “The Two Ecologies/The Three Ecologies.” NB the phrase “the pattern which connects” I have also borrowed from a later Bateson work.

Gregory Bateson, edited transcript, box 27, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

ibid.

Ibid.

Gregory Bateson, letter to Ronnie Laing, July 21, 1966, box 27, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Gregory Bateson, edited transcript, box 27.

Ibid.

Gregory Bateson, letter to Ronnie Laing, July 21, 1966.

The Anti-University found a second life in the UK student occupations of 2010-11 and continues in some form today: https://antiuniversity.org/history/

Jon Goodbun

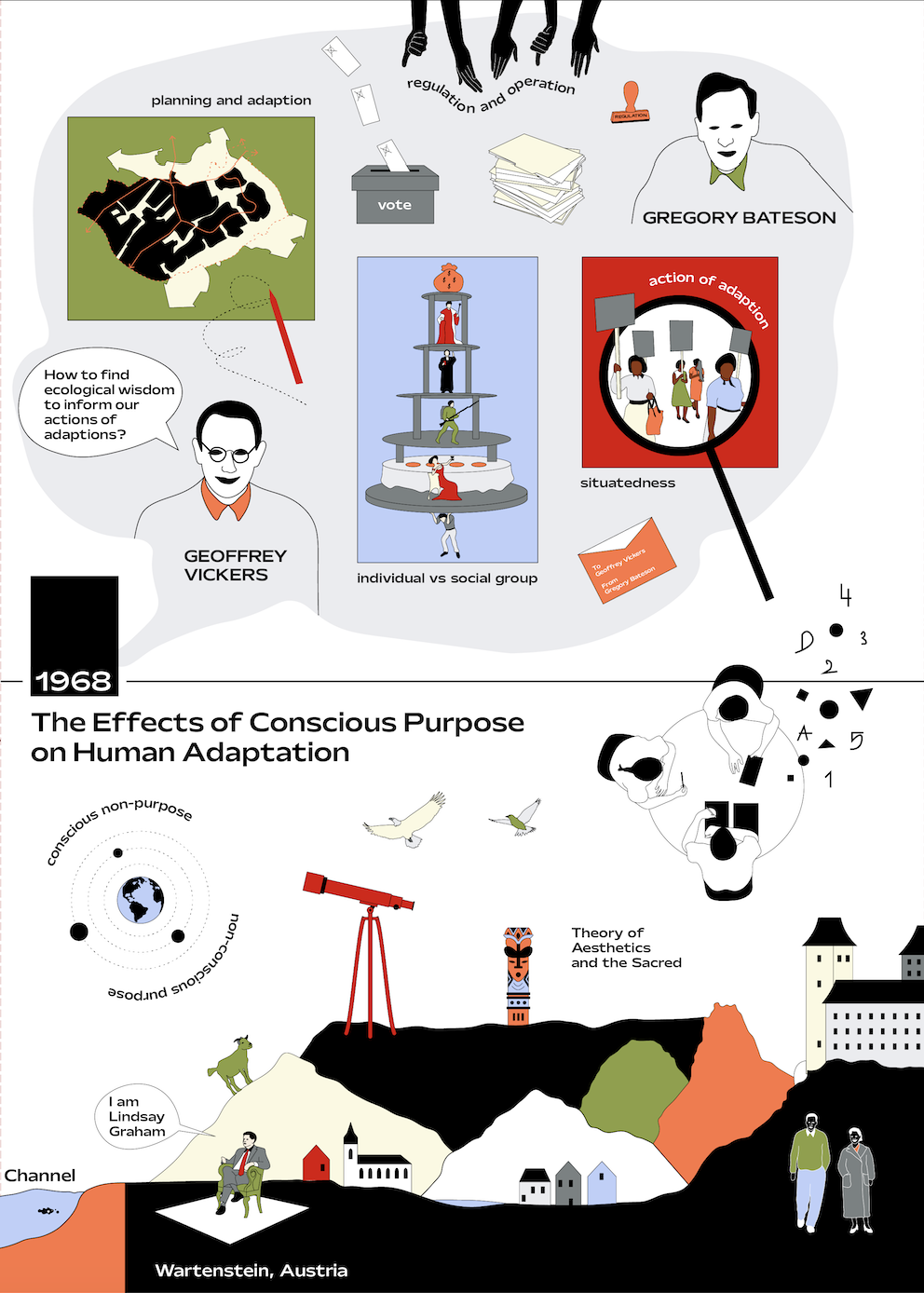

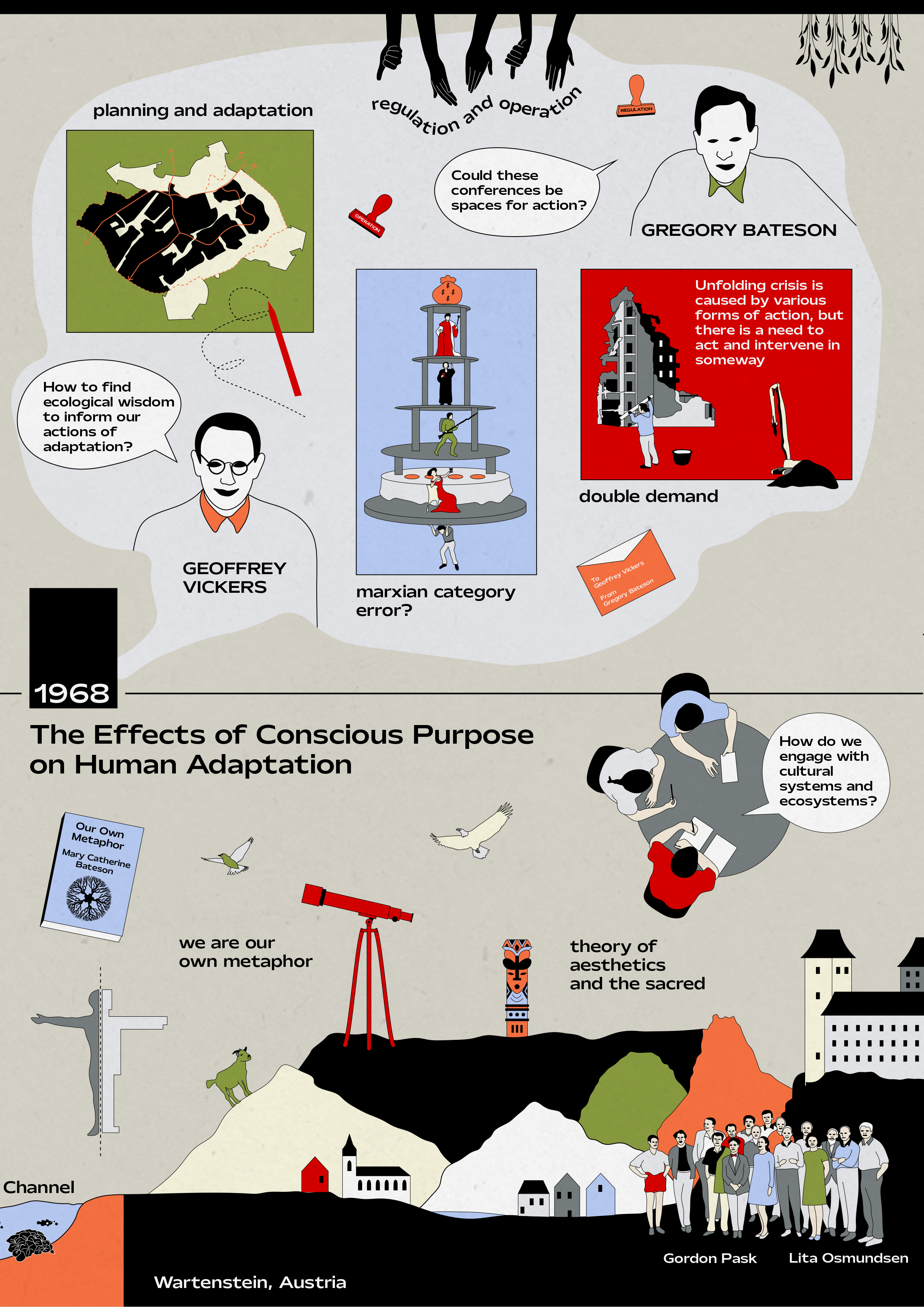

Wenner-Gren Conference on the Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation: Burg Wartenstein 1968

Gregory Bateson had an exceptionally productive summer in 1967. His performance at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress found an engaged audience for his emerging research questions, concerning the formal conditions—contradictions, paradoxes, double binds—of human consciousness in relation to ecological and social systems. Just as importantly, he had presented many of the same questions in a different context at the Wenner-Gren conference on Primitive Art and Society just a few weeks previously, and moreover, had started there a productive dialogue with Wenner-Gren’s Director of Research Lita Osmundsen, regarding the possibility of hosting a Wenner-Gren conference on “Consciousness” in the summer of 1968.

Leaving London at the end of July, Bateson enthusiastically picks this up again, sending Osmundsen a hand-written letter, boldly stating:

If truly the purposive-conscious view of self, society and eco-system necessarily distorted (unless corrected by what our conference will disclose); & if truly, this distortion when implemented by technology will inevitably start ecological and other runaways—then, nations, political policies, large industrial and financial pseudo-persons are biological monstrosities.[1]

By the end of August 1967, Bateson and Osmundsen had agreed a clear plan for an event to be held the following summer, at the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research’s Burg Wartenstein conference centre in Austria, and he had already written what would become his position paper for the conference, then entitled “The Role of Consciousness in Human Adaptation.”[2] It is an extraordinarily clear and powerful document, a twenty point list, which distils the core arguments that he had made at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress in 1967—but notably now amplifying the importance of the question of “how systems learn,” which he frames as a clear research project.

This paper, or “formative memorandum,” as he and Osmundsen referred to the text, would be included almost unchanged in his seminal 1972 essay collection Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Bateson is in fact fighting several battles here. Clearly, of course, he is continuing to express his frustration with, and to build his analysis and critique of, contemporary western modes of human existence in the face of the reality of an unfolding ecological crisis, perhaps compounded with a cultural crisis, which he felt demanded an appropriate response from him. In parallel, he finds himself in the middle of various attempts by others to propose adaptation responses in the form of political programmes and plans, such as he encountered in London the previous summer, but which he felt were often still trapped in the same damaged western thinking and lack of systemic wisdom.

Bateson is clear that he found in cybernetics a significant new, but incomplete, tool kit for understanding this condition, and that he had a key new piece of the puzzle:

It has always been clear that the philosophical ground of cybernetics would entirely change our social philosophy and ethics but I think our conference will be [the] first big step towards doing this.[3]

However, to achieve this, he must also fight a battle to defend and nurture what we might call a critical legacy within cybernetics, a critical cybernetics, which recognises some important new distinctions within the complexity of issues associated with what Rosenblueth, Weiner and Bigelow had described as “purpose” in their seminal 1943 paper.”[4]

Historically, cybernetics had studied what we might call “unconscious purpose,”[5] with much work done on understanding the emergence of goal-oriented behaviour of non-conscious systems (living, social and mechanical) which have, or behave as if they have, their own goals and objectives. Bateson was of course not only supportive of this research, but he had also been a key collaborator in its development around the Macy Conferences of the 1940s and 50s, along with Warren McCulloch, Norbert Weiner, Ross Ashby, Heinz von Foerster, Margaret Mead and others. However, he saw this project as not simply incomplete, but barely started.

Importantly, Bateson thought that the cybernetics needed to confront “the problems of biological philosophy and organization theory which this matter proposes,”[6] and was therefore increasingly concerned with what he saw as the growing instrumentalisation of cybernetics, by what he broadly described as “engineers.” Increasingly focusing in on this critique, he re-named both the planned event and his position paper, returning to “Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation,” a title he had first given the proposed event in the hand-written letter he first sent to Osmundsen from London after the Dialectics of Liberation Congress.[7]

His shift towards the term “conscious purpose” rather than “consciousness” was no doubt in part to clarify the focus of his attack, towards a particular historical form of consciousness, and to leave open a space for a wiser, more-than-purposive “aided-consciousness.”[8] But it was also, I think, to open a new line of attack on what was becoming an increasingly solution-engineering driven field of cybernetics.

In October 1967, Osmundsen agreed to fund a trip to Washington for Bateson to attend the inaugural meeting of the American Society of Cyberneticians (ASC), chaired by his old Macy colleague Warren McCullouch, and called: Purposive Systems: The Edge of Knowledge. Returning from the event, Bateson writes to Osmundsen again:

The cybernetic conference was well worth attending, if only because I needed to know the direction in which they are all going. I am sorry to say that they seem to be moving away from the rather wide philosophic view which was characteristic of the founding fathers – Wiener, McCulloch, etc. The engineers seem to be stealing the stage from the philosophers.[9]

The concept of “conscious purpose” then, was a conceptual missile—“the explosive memorandum”[10] he called his position paper—aimed directly at revealing the important distinctions within and between conscious and unconscious goal-driven, purposive systems in cybernetics. Whilst his summary of the inaugural 1967 ASC event was perhaps a little unfair—this was after all the event at which Margaret Mead presented her seminal “Cybernetics of Cybernetics” paper, which became an influential text within the broader shift towards second-order cybernetics! Nonetheless, his fears were perhaps later confirmed, when in the autumn of 1968 he had a paper proposal rejected for the second ASC conference, this time testing the title “The Effect of Limited Purpose on Human Adaptation.”[11]

It is significant that he invited both McCulloch and Ashby—two of the foundational philosopher-cyberneticians—to his 1968 Wenner-Gren event, precisely to discuss purposive consciousness in distinction to purposive systems more broadly. McCulloch did attend and contribute. Ashby declined, which was a “big blow” to Bateson, although his replacement, the eccentric London-based theatre and educational experimentalist Gordon Pask, made a significant enough contribution to the group, whose final participants included Frederick Attneave (a psychologist who presented on the cybernetics of runaway populations), Barry Commoner (a botanical ecologist who Bateson asked to open proceedings with an account of the environmental crisis), Gertrude Hendrix (animal training and the teaching of mathematics), Anatol Holt (mathematics and computing), Will T. Jones (anthropologist and organiser of the “Worldviews” conference that same summer), Bert Kaplan (psychologist and chair of the History of Consciousness programme at UC Santa Cruz), Peter H. Klopfer (ecology and animal behaviour, working on the use of space by animals), Horst Mittelstaedt (biochemistry and veteran of the Macy “Group Processes” events), Bernard Raxlen (a psychiatrist who presented films from the Portuguese Azores documenting pattern repetition and redundancy across buildings, streets, and families there), and Theodore Schwartz (an anthropologist who presented on Melanesian cargo cults.)

Importantly, Gregory Bateson’s daughter from his marriage with Margaret Mead—Mary Catherine Bateson—was present in multiple roles: as a participant (listed as a linguist), as a representative of the changing sensibilities of a younger generation, and also as the “recorder” of the event. Her participation and interventions in the proceedings, and her account of them after, have given an important afterlife to this event, and made the first of what would become a significant lifelong contribution to second-order cybernetics and beyond. Her “personal account” of the proceedings of the summer of 1968, which were published in 1972 as Our Own Metaphor (the same year as Steps to an Ecology of Mind), initiated an extended and significant period of engagement between the two, until his death in 1980. Her presence both helped to bridge the space between the street-fighting urgency of the dialogue at the Dialectics of Liberation the year before, and the more rarified airs of the ivory castle of Burg Wartenstein. In the introduction to her account, she wryly noted that:

As an adolescent, I had berated my father for his cynically stated reluctance to become involved, his sense that the universities and the political and economic structures of the world were irremediably steeped in folly. Now, in the emerging ecological crisis, he had decided to care again, so this would be our first collaboration in commitment as well.[12]

The event was organised in accordance with some research methodologies that Wenner-Gren and Osmundsen had developed: a small group for an extended unbroken residential stay, with papers shared and read in advance, and not read at the event. Bateson clearly thought that he could work productively and experimentally with this format:

What is unusual about our conference is that we start from a theme or thesis.

I believe that this is an interesting experiment. I believe that the thesis – right or wrong – is non-trivial; and that whatever grows from it, even its rebuttal, will be non-trivial.[13]

And in 1968 at least, it seemed to work. Over a series of seven days the group found various ways to approach what Bateson, in correspondence with Geoffrey Vickers in the lead up to the event, had described as “a nasty double twist”:

The problem of the cultural determination of the ratio between concentration on “operations” and concentration on “regulation” is a very interesting matter to which, I hope, we shall give a lot of attention…. The problem with which we have to deal… contains a nasty double twist. We… face crises precipitated by operationalists. But crisis promotes operationalism, though the real need is for regulation.[14]

Bateson was happy with the deliberately slow progress made, and 1968’s Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation would become the first of a series of conferences that Bateson would develop with the Wenner-Gren Foundation over the next few years.

In many ways it was Mary Catherine Bateson’s critical contribution—that the group could take itself as a cybernetic model of its subject matter—which both grounded her father’s growing exploration of a totemistic aesthetics of empathy,[15] whilst effectively enacting her mother, Margaret Mead’s, presentation on “The Cybernetics of Cybernetics” at the first ASC conference, the previous autumn.

Gregory Bateson, letter to Lita Osmundsen, July 27, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.Attached to a covering letter to Lita Osmundsen, August 31, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Gregory Bateson, letter to Lita Osmundsen, July 27, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.See A. Rosenblueth, N. Weiner a J. Bigelow, ‘Behaviour, Purpose and Teleology’ in Philosophy of Science 10 (1943), pp.18-24.

Although that particular phrasing was never used as far as I am aware.

Gregory Bateson, letter to Lita Osmundsen, August 31, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.Gregory Bateson, letter to Lita Osmundsen, July 27, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives. In fact, Bateson also retrospectively renamed his 1967 Dialectics of Liberation paper for publication in David Cooper’s edited collection, replacing “Consciousness” with “Conscious Purpose.” NB I am indebted to many conversations with Ben Sweeting around this material, and his reading of a parallel story of an arc of thinking in Bateson’s work at this time, which ran through “consciousness,” “conscious purpose” and “epistemology.” Refer to e.g. Ben Sweeting, “Conscious Purpose and Design” (unpublished manuscript, January 2025).In his paper at the Primitive Art conference in 1967 he used the terms “aided-“ and “unaided-consciousness.”

Gregory Bateson, letter to Lita Osmundsen, October 31, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.Gregory Bateson, letter to Lita Osmundsen, October 18, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.Gregory Bateson, paper proposal attached to letter to Carl Hammer, VP ASC, June 26, 1968, and rejection letter dated September 3, 1968, box 1, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.Mary Catherine Bateson, Our Own Metaphor, 1972 (Hampton Press, 2005), 12.

Gregory Bateson, letter to initial group of accepted invitees, December 27, 1967, box 36, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Gregory Bateson, reply to Geoffrey Vickers, Jan 30, 1968, Gregory Bateson Papers,

UCSC Special Collections and Archives.We can trace this from Bateson’s question, building on Martin Buber, whether we can build I/thou relations, based on love, rather than I/it relations based on use and purpose—both with each other, and as a route to learning to love and empathise with the non-human.

Ben Sweeting

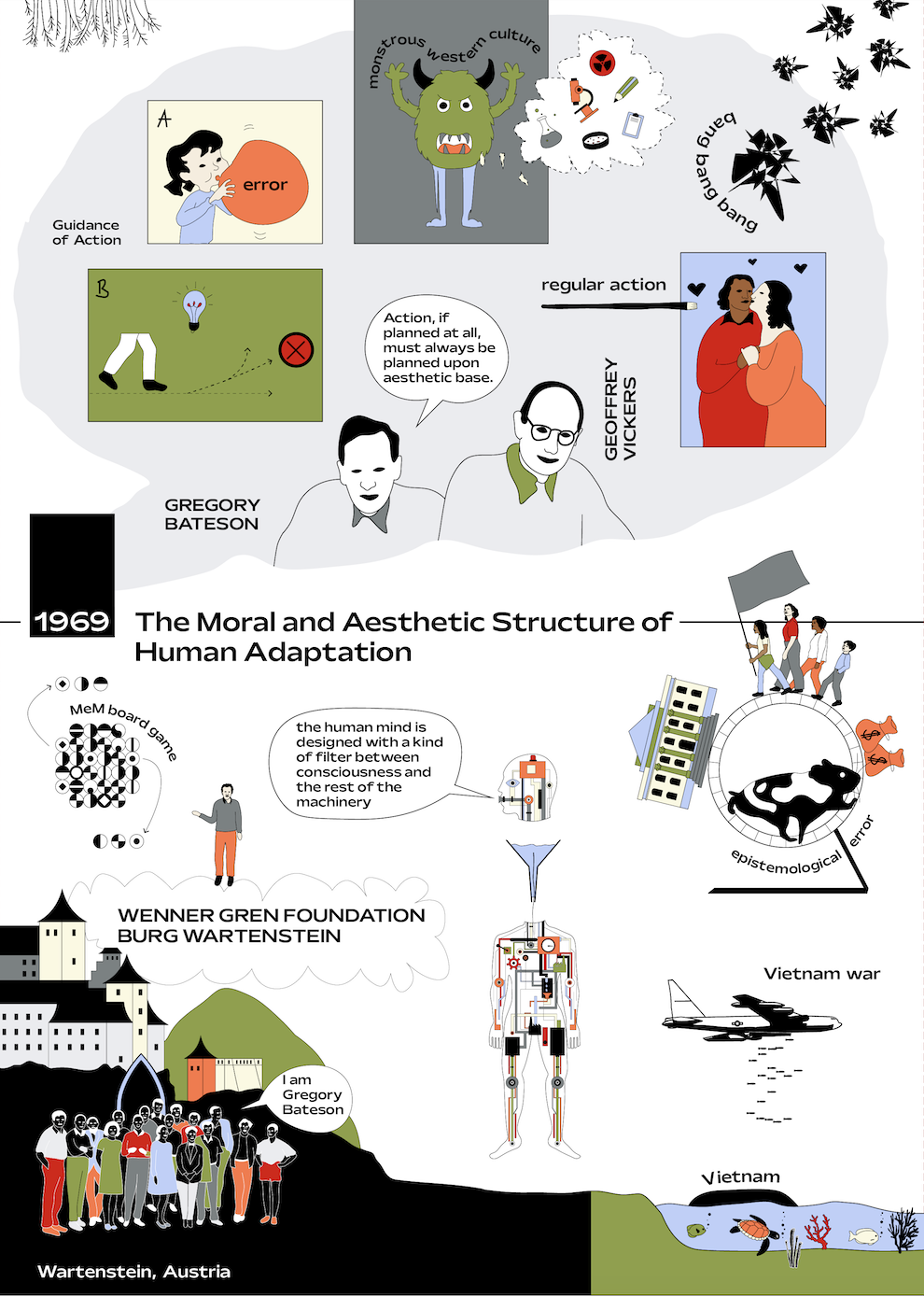

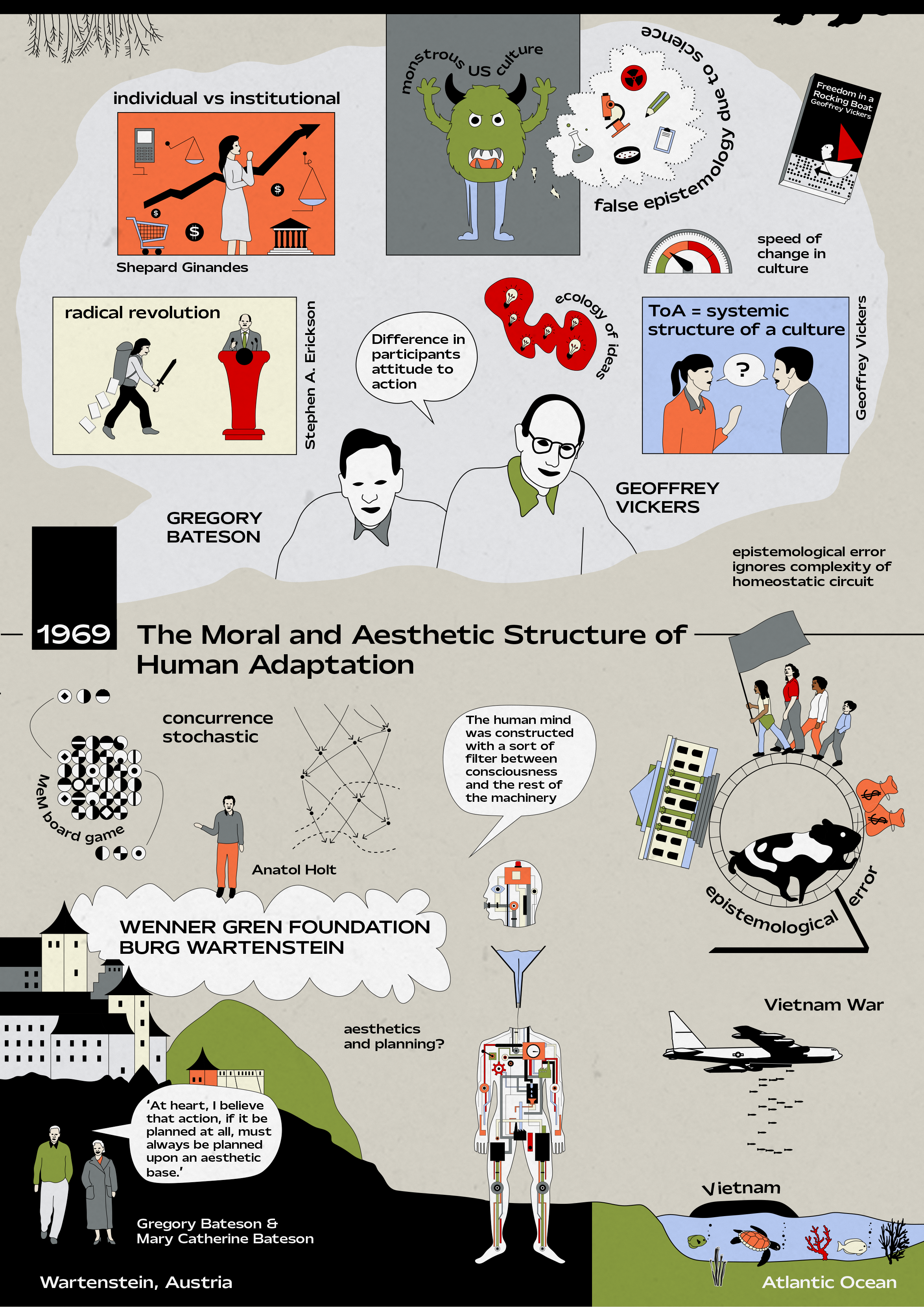

Wenner-Gren Conference on the Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation: Burg Wartenstein 1969

The Wenner-Gren conference titled The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation took place July 19-28, 1969, chaired by Gregory Bateson.[1] It was conceived as “a second session”[2] of The Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation, the Wenner-Gren conference Bateson had led the previous year. Both events were coordinated by Lita Osmundsen, the Wenner-Gren foundation’s Director of Research, and hosted at Burg Wartenstein, the castle in Austria that served as the foundation’s conference venue. Although conceived as a sequel, Mary Catherine Bateson reflected that the various changes in the group of participants meant that the second event “was not really a continuation of the first.”[3] Amongst those participants from Effects who did not return were Will Jones and Fred Attneave, both of whom had expressed reservations about the unconventional format.[4] Gertrude Hendrix was another who did not attend, leaving Mary Catherine Bateson as the only woman participant at the 1969 event.[5] Along with Mary Catherine Bateson and her father, the others to participate in both events were Barry Commoner, Anatol Holt, Bert Kaplan, Peter Klopfer, Warren McCulloch, Horst Mittelstaedt, Gordon Pask, and Theodore Schwartz. Six new participants joined for the 1969 event: film director Guy Brenton, philosopher Stephen A. Erickson, psychiatrist Shepard Ginandes, marine zoologist Taylor Pryor, anthropologist Roy Rappaport, and systems theorist Geoffrey Vickers.

The 1969 conference picked up from questions about action that had been left unresolved the previous year. During Effects, Gregory Bateson had resisted the discussion moving towards action in ways that he felt were premature, notably when other participants brought up the need for public relations campaigns.[6] In Our Own Metaphor, Mary Catherine Bateson offers an interpretation of her father’s concerns about public relations in terms of what would now be understood as greenwashing, where environmental concerns have “provided the advertising industry with a new idiom and new fears to prey on.”[7]

In the memo setting out the agenda for the 1969 conference, Bateson centred questions of action: “What is lacking is a Theory of Action within large complex systems, where the active agent is himself [sic] a part of and a product of the system.”[8] Bateson also used the memo to articulate his reasoning for having previously held the group back from planning action:

I believed that we had what the Bible calls “beams” in our own eyes—distortions of perception so gross that to attempt to remove “motes” from the eyes of our fellow men [sic] would be both presumptuous and dangerous.[9]

For Bateson, it was significant that the members of the conference were themselves party to the erroneous premises of Western civilization as they may well replicate these errors in whatever plans they devise. In the memo and subsequent correspondence, Bateson also notes how these erroneous premises “are themselves buttressed by homeostatic mechanisms,”[10] such as habit, vested interests, and institutions. As with other homeostatic systems, interventions to correct only specific variables may lead to distortions in the whole, leading to a dilemma over how to enact change. Setting out “bald-headed to correct these epistemological errors we would in fact be committing an error of the same general type – ignoring the homeostatic circuits.”[11] Given this, should one act to prevent undesirable trends or, alternatively, feed them to raise public awareness of underlying problems? Perhaps even changing public opinion doesn’t go far enough: “There is also a major question as to whether public furor over e.g. pollution does anything to correct the underlying epistemological errors.”[12]

Bateson’s considerations of action led him to themes of metaphor and aesthetics. Metaphor had become central to the 1968 conference, as emphasised in Mary Catherine Bateson’s narrative account.[13] Bateson drew on this in the 1969 conference memo, suggesting that “mental processes in which the total organism (or much of it) is used as a metaphor”[14] may help mitigate or avoid the sorts of error with which the conference was concerned. Bateson had referred to something similar in “Conscious Purpose Versus Nature,” setting out possible ways in which one might respond to the distortions of conscious purpose by using oneself as a “cybernetic model,”[15] including the creativity and perception of art amongst these. For the 1969 conference, Bateson continued these lines of thought by centring aesthetic questions in relation to the need for a theory of action, remarking in the invitation letter: “At heart, I believe that action, if it be planned at all, must always be planned upon an aesthetic base.”[16]

The conference itself is documented in a commentary written by Vickers, based on his notes during the event. Vickers records that the introduction session made apparent significant differences amongst the participants in terms of their attitude to action and the extent to which they agreed with Bateson’s way of problematising false epistemology. Vickers notes that “whilst most people seemed to go along with this [Bateson’s position] intellectually, there were, I think, wide and unspoken differences in the extent to which they went along emotionally.”[17] Taylor Pryor “accepted the policy making and executive machinery of his society” but hoped for action to be informed by more effective ecological insights; for Commoner, action was “primarily opposition to official policy, in so far as it is un-ecological”; Erickson “conceived himself to be acting in a revolutionary situation” on campus, “for which built-in mechanisms of change might not prove adequate; but so far they had served”; Ginandes, who ran a centre for adolescents that combined creative arts education with therapy, was concerned with action at a personal level, and for this purpose “could take the culture as alien but given.”[18] Amongst the others, Vickers notes what he perceived as fear of acting on too large a scale, which he interpreted as “a particularly American distrust of any kind of action above the level of personal interaction.”[19] Vickers describes his own position in terms of a search for a theory of action that would “represent the systematic structure of a culture (the ecology of ideas) and thus disclose how it could most effectively change itself.”[20]

After the introductions, Bateson began by reading the story of the Native American Church’s peyote ceremony that anthropologist Sol Tax had told at one of the earliest Wenner-Gren conferences, Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth.[21] The ceremonies of the Church make use of the peyote cactus, which “is frequently thought of by white folks as a narcotic or a drug”[22] and was being prohibited in some states. Tax offered to make a documentary film that could help defend the legitimacy of the ritual so that it would be protected by laws of religious freedom. However, the members of the Church were concerned that the ceremony itself would be disturbed by being filmed and ultimately decided against it, perceiving that “it is nonsense to sacrifice integrity in order to save a religion whose only validity—whose point and purpose—is the cultivation of integrity.”[23]

Tax refers to the film as a “public relations instrument” and notes that the “story illustrates the impossibility of planning for people instead of having them plan for themselves.”[24] However, judged from Vickers’ notes, these resonances with the discussions around planning and public relations from the 1968 conference did not come across in Bateson’s retelling. Bateson later described his intention in bringing this story to the conference participants as being “to lay on them a standard of integrity”[25] as they began their discussions on the moral and aesthetic. No significant discussion followed Bateson’s telling of the story:

My gathering of scientists took a look at the story and panicked. They thought that the Indians were perhaps being unreasonable or overzealous. Perhaps “holier than thou.” And so on. They took a worldly view of the whole story. So I lost my conference that first morning and after that for eight days we were trying to find our way back to an integration of the group. We never did succeed in doing so.[26]

Vickers, for one, did not understand the relevance to the meeting. Seeking to interpret the story as a direct analogy, Vickers thought the juxtaposition between integrity and survival was not relevant to the conference. For the matters being considered, survival and integrity were aligned: “we were seeking to recover our integrity, which we had lost and its recovery was also the road to survival.”[27]

Despite the focus of the conference on aesthetics, Bateson had not invited specialists in this topic to join his “gathering of scientists,” remarking in the conference memo that “some reading of the works of those who claim such competence [in aesthetics] has not convinced me that they know much more than we.”[28] Bateson went further in a November 1968 letter to Will Jones, drawing a parallel with the clinical fallacy in psychiatry:

Like psychiatrists, they [experts in aesthetics] are unable to look at the total spectrum of relevant phenomena because they are obsessed with the need to classify the phenomena into good and bad. The psychiatrists look only at the bad in their field – the aestheticians look only at the good in theirs.[29]

When Bateson sent a copy of his then still unpublished paper “Style, Grace, and Information in Primitive Art” to several interested scholars,[30] the most substantial reply he received, coming a few weeks before the 1969 conference, was from architectural historian James Ackerman. And, indeed, Ackerman focused on differentiating “great” works of art, a question that, for Bateson, was beside the point.[31]

Although Bateson did not invite academic specialists in aesthetics, there was someone amongst the group who had recently exhibited in a high-profile art exhibition: Pask. The 1968 Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Arts, curated by Jasia Reichardt, had opened in August 1968, shortly after the Effects conference which had taken place that July. The exhibition included the interactive installation Colloquy of Mobiles completed by Pask with Yolanda Sonnabend, Mark Dowson, and Tony Watts. Pask’s accompanying text set out his idea of an “aesthetically potent environment,” in which he understood aesthetics in terms of the “relation between the environment and the hearer or viewer.”[32] To some extent, Pask’s description parallels aspects of Bateson’s connection between aesthetics and metaphor: the aesthetically potent environment guides the hearer or viewer and “in a sense, it makes him [sic] participate in, or at any rate see himself [sic] reflected in, the environment.”[33]

One of Pask’s contributions to the conference was “to chide the meeting for its pessimistic mood.” The conference was worried about “auto-catalytic processes getting out of hand” but “there are gracious, as well as vicious circles.”[34] Pask highlighted the possibilities of education in this regard. While, according to Vickers, Pask’s intervention “made a marked difference to the tone of the conference,” the next day (the last programmed day of the conference) Bateson expressed his dissatisfaction with the progress that had been made.[35] Osmundsen declined to support a further sequel, later reflecting that “the conference didn’t click. It didn’t have an impact on the participants.”[36]

Keywords: Aesthetics, Theory of Action, Integrity, Gracious Circles

I have used the spelling “aesthetic,” following Bateson’s use in correspondence, the conference memo, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation website. However, the spelling “esthetic” is used in the conference booklet of background information on participants. Box 36, folder 1480, document 1480-4, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Letter from Gregory Bateson inviting participation in the 1969 conference, November 5, 1968, box 36, folder 1480, document 1480-1, a, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Mary Catherine Bateson, Our Own Metaphor: A Personal Account of a Conference on the Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation (Hampton Press, 2005), 313.

Letter from Will Jones to Gregory Bateson, November 26, 1968, box 36, folder 1480, document 1480-2, h, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives. Letter from Fred Attneave to Gregory Bateson, January 4, 1969, box 39, binder 4, document B4-1, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Osmundsen was also present but not as a participant.

M. C. Bateson, Our Own Metaphor, 141-143.

M. C. Bateson, Our Own Metaphor, 142.

Gregory Bateson, “The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” conference memo enclosed with letter dated November 5, 1968, box 39, binder 4, document B4-6, d, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives. Emphasis original. An abridged version of the memo is published in A Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind, ed. Rodney E. Donaldson (Triarchy Press, 2023). Jon Goodbun has brought attention to the significance of Bateson’s concern with a theory of action within this often-overlooked text. Jon Goodbun, “Gregory Bateson and the Political” (unpublished manuscript, November 2024); Dulmini Perera, Jon Goodbun, Phillip Guddemi, and Fred Turner, “Gregory Bateson and the Political,” Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design RSD11, https://rsdsymposium.org/gregory-bateson-and-the-political/

G. Bateson, “The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” conference memo enclosed with letter dated November 5, 1968, d.

G. Bateson, “The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” conference memo enclosed with letter dated November 5, 1968, e. C.f. Letter from Gregory Bateson to conference participants, April 30, 1969, box 39, binder 4, document B4-19, b. Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Letter from Gregory Bateson to conference participants, April 30, 1969, b.

Letter from Gregory Bateson to conference participants, April 30, 1969, b.

M. C. Bateson, Our Own Metaphor.

G. Bateson, “The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” conference memo enclosed with letter dated November 5, 1968, h.

Gregory Bateson, “Conscious Purpose Versus Nature,” in The Dialectics of Liberation, ed. David Cooper (Penguin, 1968), 48.

Letter from Gregory Bateson inviting participation in the 1969 conference, November 5, 1968, b.

Geoffrey Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44. The Moral and Esthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” box 36, folder 1481, document 1481-3, b, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44,” b.

Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44,” c.

Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44,” b.

William L. Thomas Jr. (Ed.), Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth (University of Chicago Press, 1956), 950-954. A version of the Sol Tax story is presented in Gregory Bateson and Mary Catherine Bateson, Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred (Hampton Press, 2005), 71-74.

Thomas, Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth, 952.

G. Bateson and M. C. Bateson, Angels Fear, 75.

Thomas, Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth, 952, 954.

G. Bateson and M. C. Bateson, Angels Fear, 75.

G. Bateson and M. C. Bateson, Angels Fear, 75-76.

Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44,” q.

G. Bateson, “The Moral and Aesthetic Structure of Human Adaptation,” conference memo enclosed with letter dated November 5, 1968, j.

Letter from Gregory Bateson to W. T. Jones, November 8, 1968, box 36, folder 1480, document 1480-2, g, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Bateson was encouraged in this matter by Roger Keesing, who suggested Bateson send the manuscript to James Ackerman, Rudolf Arnheim, György Kepes, Cyril Stanley Smith, Marx Wartofsky, and Paul Weiss. Letter from Roger M. Keesing to Gregory Bateson, May 12, 1969, box 18, folder 759, document 759-19, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Letter from James Ackerman to Gregory Bateson, June 24, 1969, box 1, folder 10, document 10-2, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Gordon Pask, “The Colloquy of Mobiles,” In Cybernetics Serendipity: The Computer and the Arts, ed. Jasia Reichardt, special issue of Studio International (1968), 34.

Pask, “The Colloquy of Mobiles,” 34.

Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44,” p-q.

Vickers, “Burg Wartenstein Symposium No. 44,” q.

Personal communication from Lita Osmundsen to David Lipset, quoted in David Lipset, Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist (Prentice-Hall, 1980), 268.

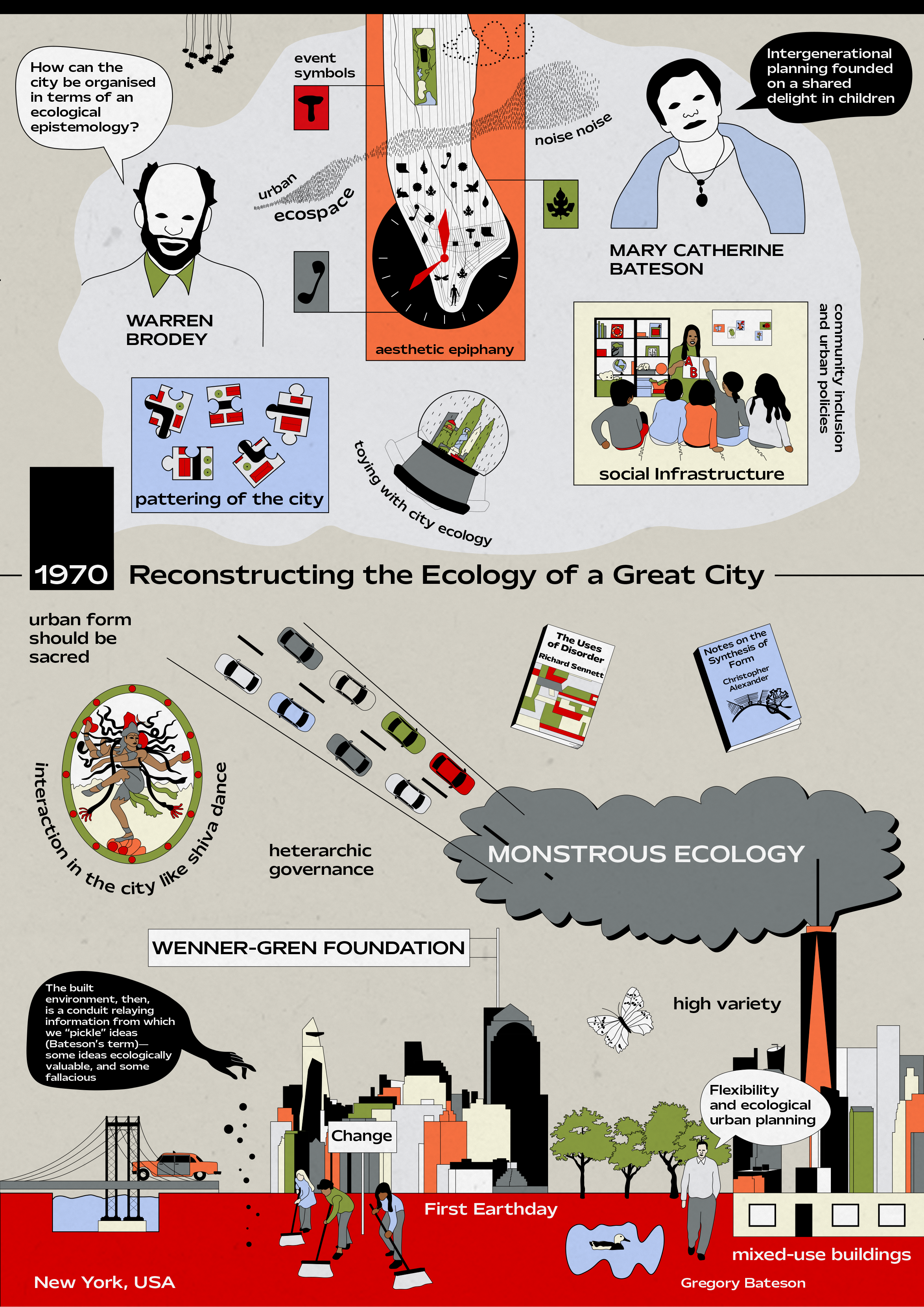

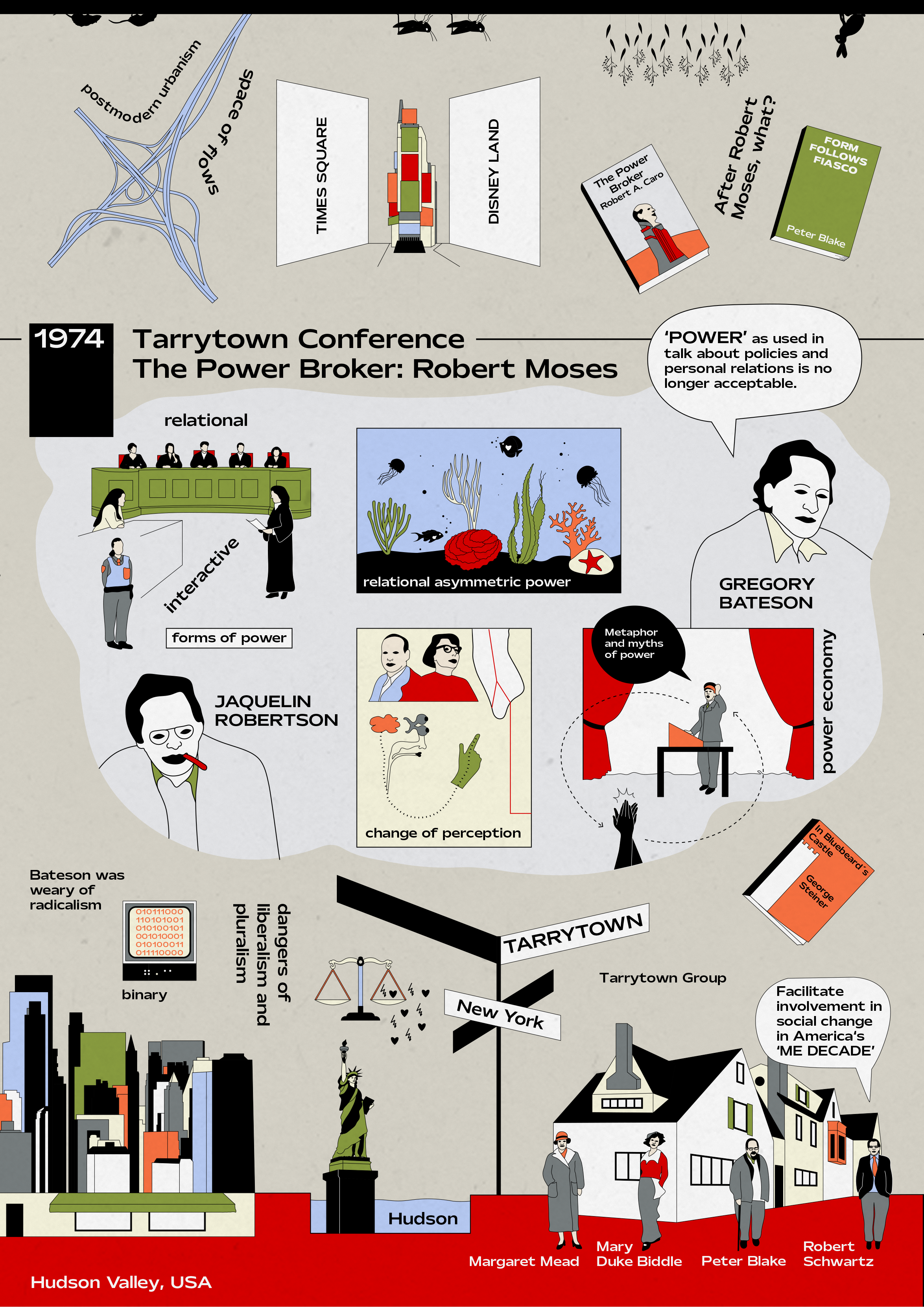

The 1969 conference titled “Human Distress and Rapid Social Change” took place over three days between December 14-17 at Princeton. Organised by Vic Gioscia, a senior sociologist at the Department of Psychiatry at Roosevelt Hospital and the executive director of The Center for the Study of Social Change, the purpose of the conference was to evaluate whether the Center should exist at all.[1] The Center was affiliated with the hospital and was founded the same year by Gisocia and other therapists who wondered whether particular institutional forms could promote actions, methods and tools capable of addressing the distress caused by runaway conditions of social and environmental change. Bateson’s psychological and anthropological work on change, distress and pathology enabled him to play a central role at the conference as a kind of planetary psychiatrist.

Other attendees included psychiatrists such as Albert E Scheflan, Edgar Auerswald and Harley Shands.[2] Gioscia also invited media artists. Frank Gillette was a founding director of the 1969 Raindance Corporation (set up as a counter to Rand Corporation) and the countercultural media magazine Radical Software. Paul Ryan was a video artist and also a member of the Raindance foundation. The relationship between planned environments and action was more directly problematised by Warren Brodey, a psychiatrist, a technologist and one of the founders of the Environmental Ecology Lab (EEL) which had by this time morphed into a smaller experimental endeavour Titled Ecology, Tool, Toy Company. Brodey, though not a trained designer, was most active in the then emerging conversations on “information environments” that were influencing architecture. [3] Bateson prompted the participants not to limit the inquiry to “screwdriver questions,” (i.e., questions about specific forms of action necessary to avert crisis) but to also include “ecological questions.”[4] Ecological questions were of a different order and took a broader view of the relationships between distress, rapid environmental change and the pathologies created by Western epistemologies. [5]

Bateson’s recently published paper on The Cybernetics of ‘self’: A Theory of Alcoholism, attempted to provide a systemic explanation for pathological action, and had made the rounds at the conference. It proved a useful resource for thinking about self, pathology and ecology. At the meeting, Bateson stressed that the ecological discourse itself was not impervious to such dysfunctionality, and that it had become a “sick science” by getting mixed up with the economics of energy. He was concerned with how ecological discourse was obsessed with quantities, overlooking qualitative aspects of living processes which could only be grasped by examining communication relations. Over the course of the three days, a number of presentations made connections between environments and distress. Examples ranged from New York City traffic to case studies of unplanned housing in London and the issues of health service systems. Bateson’s work prompted a closer look at how the organisation and balance of these systems were both equally dependent on a broad range of semiotic-communication processes. In other words, they related to sense, habit and value frameworks without which they could not persist. All life forms perceive, and life is constituted as a web of semiotic relationships. One can read Bateson’s work as an early attempt to acknowledge the role semiotic webs of communication, play to help environmental practitioners perceive and act on a system’s flexibility.[6] New York residents, the smog, buildings, video cameras, and computers all participated in the production and transformation of ecologies. This implies that technologies and tools all participate in runaway conditions, creating different forms of feedback which contribute to the production of ecosystemic violence by programming and reprogramming the equilibrium across systems.

For Bateson, signs of distress such as pollution and smog were more than just a bio-energetic waste output but were rather a sign that a system was stuck, losing its “systemic room-for-manoeuvre” within evolving conditions of change.[7] For systems in disequilibrium, such signs of distress were how these ecological systems reported and communicated about themselves. Yet the nature of such changes presented major representational challenges. Both the human languages of nouns and the bio-energetic language of techno-science were unable to properly represent the temporally dispersed, slow, affective nature of such change or what contemporary theorists identify as “slow violence.”[8] Taking the example of DDT, Bateson argued that an understanding of the impact of DDT requires a sensitivity to slow, non-linear, and asymmetric forms of change.[9] Most of the conference participants were part of a field called kinesics, which emerged in parallel with a revival of semantic concerns in cultural theory, and which made headway in understanding communication processes associated with the unconscious and the nonconscious. Bateson was a pivotal contributor to one of the central projects in the history of kinesics: The Natural History of the Interview. He had contributed materials from his therapy practice, including video recordings of the pathological communication of schizophrenic families.[10] The growing field of kinesics borrowed from Freud an interest in the unconscious, from Gestalt theory the notion of “whole systems,” from pathogenesis an interest in communication failure, and from “theories of learning” a framework to describe how systems become stuck in pathological dynamics without the ability to learn or evolve.[11] The polluted urban sensorium of the planet and effects of systems stuck in pathology presented themselves mostly unconsciously.

To become sensitive to these pathologies meant becoming aware of the ecological context as a changing environment. This context, though omnipresent, was obscured due to the limits of language and communication. Brodey had earlier suggested that developing sensibilities towards the ecological context should be called “ecological literacy,” which prompted debate about the term. Scheflan emphasised that what is needed is not “rebuilding language” but rather building a different “territorial system” or a “territory of minds” that he defined as follows: “a system of relations between physical objects and rooms and walls and fences and rivers and behaviors around these, and behaviors among people in these in a time bound frame.”[12] Bateson would further modify Scheflan’s statement by suggesting that one needs to pay attention to the “territory of minds,” which encompassed the wider realm of habit. Questions about habit were not the same as questions of literacy. Bateson pointed across the room at how Scheflan held his pipe, and asked the others to consider where the habit of holding the pipe was located. Was it in the arm? The ear? Bateson’s radical proposition was that this habit was also partly located in the chair. Territories of minds encompassed things as well as thoughts, bodies as well as ideas, they were outside as well as inside. To change the economics of habits that have lost their openness to flexibility required an understanding of the complex ways in which “territories of minds” manifested across all of these environments.

At one point, the conference attendees had drifted into a discussion about the need for organised action. In response, Bateson reminded them, “if we are going to talk about action in a world which is systemically-ecologically fucked up, then we have to choose points in that environment in to which we are going to work.”[13] The participants saw themselves as a part of a rising “subculture” that had a relationship to the fields of systems science and cybernetics, who were exploring the possibilities of alternative forms of organised action.[14] Studies of the 1970s discourse on design and organisation reveal a broader cultural and political interest in the possibilities of forms of horizontal organisation. From versions of participatory possibilities presented around ideas of open planning to horizontal organisation defined through network metaphors the emphasis was on an erasure of hierarchies.[15] Of the attendees, Frank Gillette was the first to draw attention to the links between an ecological way of thinking and a shift away from hierarchies. He concluded: “detoxification from hierarchy is happening, and hierarchy is excluded from any kind of vocabulary that can include the ecological approach.”[16] Some responded by pointing out that hierarchies such as an “ecological subsumption of species” existed naturally in ecologies, and played a vital part in their balance and structure.[17] The problem was not with hierarchies as such, but merely their toxic aspects—the aspects which would suggest that “priests are different from people”, and that a human “is closer to an angel than a worm” —which have informed multiple forms of inequality and injustice.[18] Brodey emphasised that ontological subsumption did not necessarily denote a sequence, or a hierarchy of power relations but rather relationships that lead to specific consequences. Such relationships were not “hierarchical” but rather “heterarchical.” Heterarchical groups that have a particular purpose organise and reorganise themselves both spatially and temporally (a multi-level ordering of recursive communicative relations in space and time). [19] The concept of heterarchy is a particularly useful concept for thinking beyond the problematic flatness characteristic of many ecological theories, which, by not taking in to account the asymmetries between humans and technologies, often pave the way towards a neoliberal pluralism.

For Bateson, the Princeton conference itself embodied an interesting organisational form and became a unique site of action. The group spent almost one-third of their time discussing the relationships between the contents of their conversation and form of the conversation as well as the use of different mediums, such as video cameras, and typewritten manuscripts. For Bateson, the form one uses to communicate about ecological change must have a variety and dynamism commensurate to the site that one is looking at. Moving and changing entities needed to be engaged with in motion, or as Bateson remarked playing with a William Blake quote one must “kiss the bird as it flies.”[20] Bateson also saw this event as an exercise in working with metaphors:

Now, it is true that we in this room are the metaphor, so to speak, of the cultural changes, etc., which we are discussing. Now, the problem of how that can be represented in this room, so that we live that metaphor as an experience, in addition to living the ideas which we are discussing – this is the problem.[21]

Metaphors allowed ways of discovering similarities between different contexts, such as between the conversations in the conference room, and conversations in planning offices. Or as Brodey remarked, after having spent sleepless nights rearranging the conference tables and chairs, if you don’t fight about tables and things like that, it was impossible to move from a sick ecology to a point where people can appreciate “ecological richness.”[22] Bateson prompted the group to consider the relationship between their dialogues and media systems. “I’d rather rap with three people, and have it on tape, because I don’t think a tape on one person is very useful, really. We deal with relatedness,” stated Bateson, inviting Al and Paul to join him.[23] For artists such as Paul Ryan the Bateson Rap would equate to a process of “infolding” (represented by the topological figure of a Klein worm) whereas for a designer such as Warren Brodey it evoked responsive architectures.[24] These were envisioned as forms of therapeutic action, ways of distilling the experience of feedback via the use of technics in a way that made it possible to resist the violent, colonising effects of growing information environments.

Keywords: planetary distress, ecological questions, sick science, kinesics, semiotics, territories of minds, heterarchy, Bateson Rap, slow violence, information environment

Princeton Conference, December 14, 1969, box 80, folder I, document 12-14-69,1, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Scheflan was a professor of Psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and head of the Bronx State Hospital’s project on Human Communication. Edgar Auerswald advocated a widely-adopted “ecological” approach to family therapy, while Shands was a clinical professor of psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Dulmini Perera, “The Ecological Relevance of the Serious Time Games of Gregory Bateson, Anatol Holt and Warren Brodey” (Conference paper, American Society of cybernetics 60 Conference, DC Arts Centre, Washington, June 2024). https://events.asc-cybernetics.org/2024/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ASC60_Book-of-abstracts_2024-06-27.pdf

Princeton Conference, December 16, 1969, box 80, folder IV, document 12-17-69, C80-81, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives. ↑

Note that I have used the term Western epistemology, but Bateson often uses the term “occident” to denote the West.

Bateson used the terms informational and communication rather than the term semiotics. The more explicit readings of Bateson’s work in relationship to “semiotics” appears in scholarship that follows Bateson’s work. I have used the term semiotics in a way more similar to Felix Guattari’s use of the term in ways not limited to ‘signifying semiotics’ (that is, the linguistic symbols, of human communication) and includes‘ asignifying semiotics’ relationships operating at affective, molecular and chemical levels.

Peter Harries-Jones, Upside Down Gods: Gregory Bateson’s world of Difference (Fordham University Press, 2013), 152.; Jon Goodbun, “Flexibility and Ecological Planning: Gregory Bateson on Urbanism,” Architectural Design, no. 82 (2012): 52-55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1428.

See for example Slow violence as defined in Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Princeton Conference, December 16, 1969, box 80, folder III, document 12-16-69, B224, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Bateson joined the group at Ray Birdwhistell’s invitation and made available to the group films he had made as part of his project on families with schizophrenic children, which he had organised with John Weakland and Jay Haley at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Palo Alto.

Gregory Bateson, “Communication,” in The Natural History of an Interview, ed. Norman A. McQuown (University of Chicago Microfilm Collection: Joseph Regenstein Library, 1971), 1-40.

Ibid, 7-35.

Princeton Conference, December 16, 1969. box 80, folder III, document 12-16-69, B-136, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Ibid, B-35.

Ibid, B-59.

Mark Wigley, “Network Fever,” Grey Room 2001; (4): 82–122, https://doi.org/10.1162/152638101750420825, Non Plan: Essays in Freedom, Participation and Change, ed. Jonathan Hughes and Simon Sadler (Routledge, 2015)

Princeton Conference. December 16, 1969. box 80 folder III, document 12-16-69, B-68. Gregory Bateson Papers. UCSC Special Collections and Archives

Ibid, B-69.

Ibid, B-71.

By this time Bateson had become deeply interested in the concept of ‘heterarchy’, a concept he had borrowed from the work of neuropsychologist and cybernetician Warren McCulloch (who was a mentor for both Bateson and Brodey). McCulloch had suggested that the formal components through which meaning is drawn in the brain is heterarchical. That is, meaning is drawn from several domains within a plural chain of selections that was rendered meaningful in context. Heterarchy would later enable Bateson to see the limitations of the more neat and linear logical levels proposed in Russel’s theory of logical types.

Ibid, B-109, Original Poem by William Blake, Eternity: “He who binds to himself a joy, does the winged life destroy, he who kisses the joy as it flies, lives in eternity´s sunrise.”

Princeton Conference, December 15, 1969, box 80, folder I, document 12-14-69, 51, Gregory Bateson Papers, UCSC Special Collections and Archives.

Princeton Conference, December 15, 1969, box 80, folder I, document 12-15-69, A-236, Gregory Bateson Papers. UCSC Special Collections and Archives

Princeton Conference, December 15, 1969. box 80, folder III, document 12-16-69, B-30, Gregory Bateson Papers. UCSC Special Collections and Archives

The Klein worm is a topological form made from a self-penetrating tube and has a boundless surface. As a topological figure it resonated with the circular, reflexive logic of ecological relationships discussed by Gregory Bateson. See: Warren M. Brodey, “Biotopology 1972”, Radical Software, vol. 1, no. 4, 1971, p. 4.